What cognitive behavioral therapy can (& can’t) do for 3 a.m. wakeups after 50

+ a 5-step strategy to help you get started with CBT-I (cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia).

Section 1 – CBT-I for sleep after 50: why this matters

You’ve probably seen “CBT-I” mentioned as the non-drug treatment for insomnia. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia (CBT-I) is a structured, skills-based approach that changes habits, thoughts, and scheduling around sleep.

Insomnia becomes more common with age; roughly 20–30% of older adults live with insomnia, often for years. It’s linked with memory and concentration problems, mood changes, higher fall risk, and worse outcomes in conditions such as heart disease and chronic pain.

Major guidelines, including those supported by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, recommend CBT-I as the first-line treatment for chronic insomnia, especially in older adults where sedative-hypnotic drugs can raise fall and confusion risk.

At the same time, CBT-I has trade-offs:

It asks you to follow a very regular schedule and temporarily cut time in bed (“sleep restriction”), which can be tiring in the short term.

It takes effort: sleep diaries, behavioral changes, and challenging long-held beliefs about sleep.

Access can be limited – there are not many clinicians trained in CBT-I, and traditional one-to-one therapy is time-intensive and expensive.

In this review, we’ll walk through four recent peer-reviewed studies (2023–2025) that help answer practical questions for adults in midlife and beyond:

What can CBT-I actually do for sleep and daytime function?

How does it seem to work in the brain?

What’s realistic to expect – and by when?

Who tends to benefit most, and where are the limits?

How can you use this evidence to decide whether CBT-I is a good fit for you?

Let’s get started.

Section 2 – Study 1: Digital CBT-I for older adults (2025 randomized trial)

In 2025, Ritterband and colleagues at University of Virginia tested a fully automated online CBT-I program designed specifically for older adults, called SHUTi OASIS. They ran a three-arm randomized controlled trial with 311 adults aged 55–95 recruited from across the United States.

Participants were randomly assigned to:

Digital CBT-I only (SHUTi OASIS)

Digital CBT-I plus “stepped” human support

Online patient education (PE) about sleep and health (control condition)

Everyone met criteria for chronic insomnia (median duration ~10 years), with typical nightly difficulties falling and staying asleep. Around one-third were over age 70; most were women, white, and college-educated, and nearly all were comfortable using the internet.

The SHUTi OASIS program delivered six interactive “cores” over nine weeks, incorporating classic CBT-I elements: regular wake time, sleep restriction, stimulus control (what you do in bed and when), cognitive techniques for worries about sleep, and sleep hygiene, all delivered online with sleep diaries and tailored feedback.

Key findings for sleep

Insomnia severity dropped a lot and stayed lower.

Both digital CBT-I arms showed large improvements in Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) scores at post-treatment, 6-month, and 12-month follow-ups (effect sizes roughly −1.0 to −1.4), while the education-only group showed only small-to-medium improvements.

More people reached “response” and “remission.”

At each follow-up, older adults receiving SHUTi OASIS were several times more likely to have a meaningful ISI drop (>7 points) and to fall below the insomnia cut-off (ISI <8) than those in the education group; nearly half of those using SHUTi OASIS no longer met insomnia criteria at one year.

Sleep became more consolidated, not just longer.

Compared with education, SHUTi OASIS users had bigger gains in sleep onset latency, wake after sleep onset, sleep efficiency, number of awakenings, subjective sleep quality, and fatigue across most time points. Total sleep time increased modestly in all groups (~25–45 minutes), highlighting that CBT-I’s main impact is improving how continuous and restorative sleep feels rather than adding many extra hours.

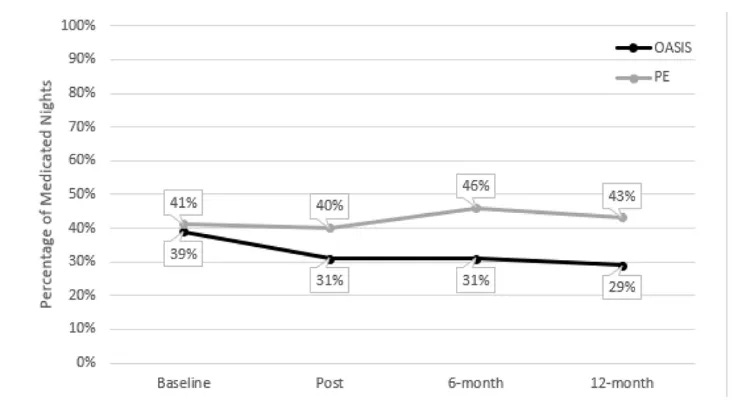

Sleep medication use went down.

The percentage of nights with sleep-aid use fell more in SHUTi OASIS than in education, even though the program did not include explicit tapering instructions.

Older adults did engage with a fully automated program.

About 63% completed all six cores during the 9-week period, and 83% completed them eventually. Engagement was strongly linked with better outcomes: those completing at least four cores had lower ISI scores at post-treatment than partial completers.

For adults 55+ with chronic insomnia, this trial suggests that a well-designed digital CBT-I program can produce large, durable improvements in insomnia symptoms and reduce reliance on sleep medication, even without live therapist sessions.

A few important caveats:

Participants were healthy enough and tech-savvy enough to handle online assessments and software. People with significant cognitive impairment, unstable medical or psychiatric conditions, or very limited internet access were excluded.

The sample was not very diverse by race/ethnicity or education, so results may not fully reflect outcomes for older adults from under-represented groups or with lower literacy.

The control group received structured sleep education, which by itself improved total sleep time and some other metrics – so part of the observed benefit in all groups may come from monitoring, education, and placebo effects, not CBT-I techniques alone.

Still, for many people over 50 who are comfortable online and want to reduce medication use, this trial supports digital CBT-I as a powerful, scalable option – with the realistic expectation that it improves how you sleep and function.

Section 3 – Study 2: CBT-I in chronic disease (2025 review and meta-analysis)

Also in 2025, Scott and colleagues at Macquarie University published a large review and meta-analysis in JAMA Internal Medicine focusing on adults with chronic medical illnesses (cancer, chronic pain, cardiovascular disease, kidney disease, diabetes, stroke, irritable bowel syndrome, and others).

They pulled together 67 randomized controlled CBT-I trials involving 5,232 participants aged 18 and older with both chronic disease and insomnia or significant insomnia symptoms. CBT-I formats included individual and group in-person therapy, self-guided digital versions, and therapist-guided digital versions.

Key findings for sleep

Insomnia severity improved by almost a full standard deviation.

Across trials, CBT-I was associated with a large improvement in insomnia severity compared with control conditions (Hedges g ≈ 0.98). That magnitude is similar to, or slightly larger than, what’s seen in non-medical insomnia populations.

Sleep efficiency and how long it takes to fall asleep improved moderately.

For sleep efficiency and sleep onset latency, CBT-I showed moderate effect sizes (g ≈ 0.64–0.77), indicating meaningful but not dramatic gains in how quickly people fall asleep and how much of their time in bed they spend asleep.

Benefits were broad across diseases and delivery formats.

CBT-I worked across cancer, chronic pain, cardiovascular and renal disease, traumatic brain injury, stroke, and mixed chronic conditions. Individual, group, and digital delivery all showed benefits; longer treatments (more sessions) tended to yield better outcomes for some sleep measures.

Treatment was generally acceptable.

The average dropout rate was about 13%, similar to or better than many other behavioral and drug trials. Participants reported high satisfaction, and reported adverse effects were infrequent.

Remission and non-response both occur.

The study reported pooled remission of ~54% with CBT-I vs ~18% in control conditions, meaning many people remit, while a substantial minority have residual symptoms.

For people in midlife and later life, chronic insomnia often co-travels with long-term health problems.

This review shows that:

CBT-I still works even when insomnia co-occurs with cancer, chronic pain, diabetes, kidney disease, or cardiovascular conditions. Improvements are moderate to large for insomnia symptoms, and moderate for efficiency and time to fall asleep – consistent with a treatment that reliably helps, but does not magically erase every sleep difficulty.

Limitations to keep in mind:

Trials often exclude the most medically or psychiatrically fragile individuals, so these data may not reflect outcomes in people with severe cognitive impairment, active psychosis, or highly unstable disease.

Study quality varied; only a minority of trials were rated as low risk of bias, and adverse event reporting was often limited, which may under-detect negative experiences (such as short-term worsening of fatigue during sleep restriction).

Many trials were conducted in specialized centers, with motivated volunteers and skilled therapists, which can make results more optimistic than typical clinic experience.

Taken together with Study 1, this review supports the idea that if you are over 50 and living with chronic medical issues, CBT-I is still a candidate – but it’s not a guarantee of full remission, and some tailoring for your specific health context is usually needed.

Section 4 – Study 3: Nurse-supported self-directed CBT-I in veterans (2024 randomized trial)

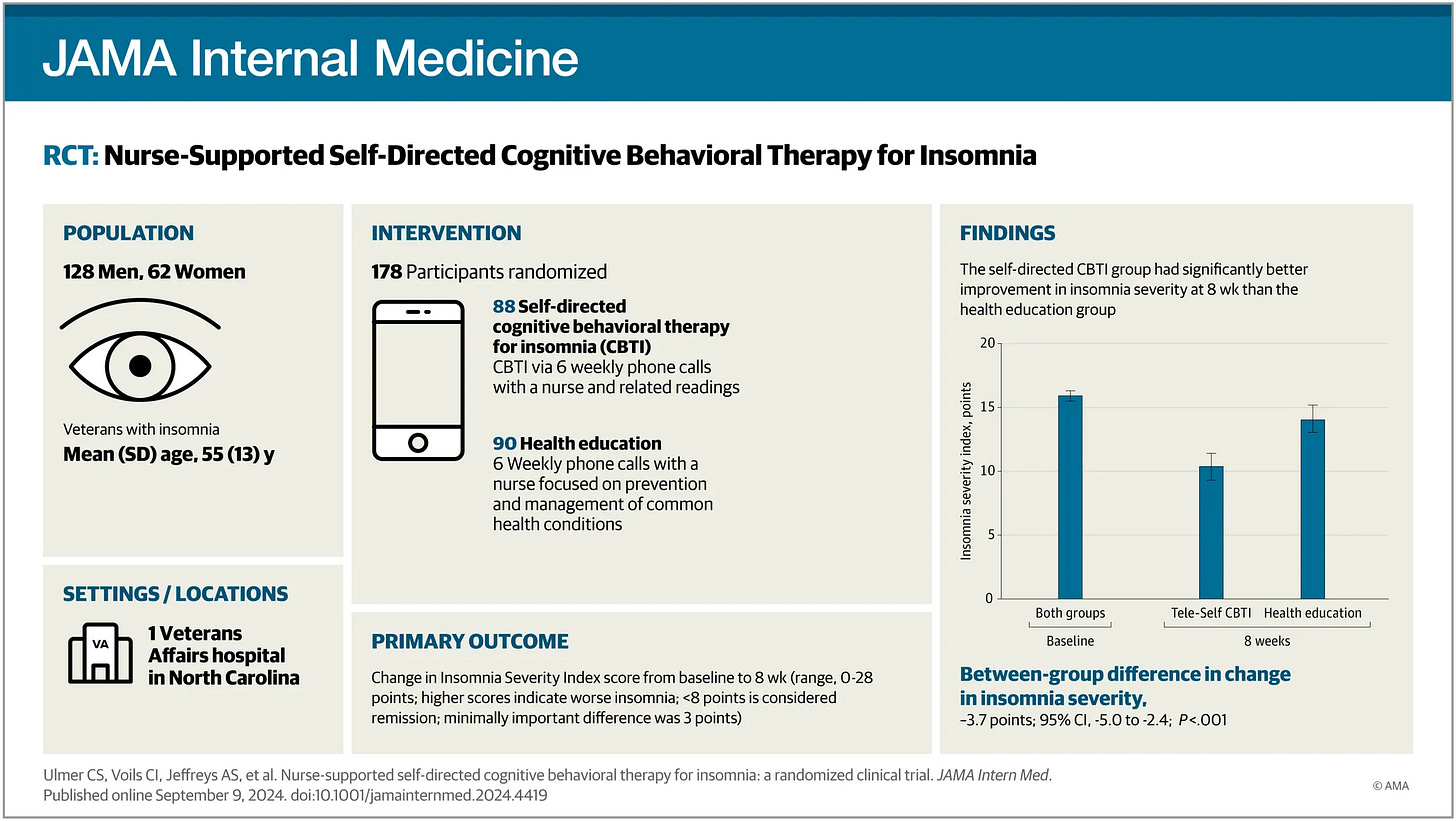

In 2024, Ulmer and colleagues at the Durham VA Health Care System tested a “lighter touch” CBT-I model in a Veterans Affairs setting. They recruited 178 US veterans with insomnia disorder (average age about 55; many over 50) and substantial comorbidity – many had a documented mental health diagnosis and most reported at least one medical condition.

Participants were randomized to:

Tele-Self CBT-I – six weekly 20-minute phone calls with a nurse plus a self-help CBT-I manual (covering sleep restriction, stimulus control, cognitive therapy, relaxation, and sleep hygiene)

Health Education Control (HEC) – the same phone schedule and attention from a nurse, but a manual focused on general health topics without sleep content

Follow-ups occurred at 8 weeks (primary endpoint) and 6 months, with outcomes assessed by ISI, sleep diaries, actigraphy, depression and fatigue scales, and treatment response/remission rates.

Key findings for sleep

Insomnia severity improved more with nurse-supported CBT-I.

From baseline to 8 weeks, ISI scores fell by about 5.7 points in the Tele-Self CBT-I group vs 2.0 points in the health-education group – a between-group difference of 3.7 points, which meets the trial’s threshold for a clinically meaningful improvement. This difference persisted at 6 months (≈2.8 points).

Sleep continuity improved on both diaries and actigraphy.

Compared with control, Tele-Self CBT-I led to greater improvements in diary-based sleep onset latency, wake after sleep onset, and sleep efficiency, and in actigraphy-measured sleep efficiency, with benefits sustained at 6 months.

More veterans responded and reached remission – but many did not.

Among those completing the 8-week assessment, about 36% of veterans in Tele-Self CBT-I met response criteria and 30% reached remission, versus 5% and 10% in the education group (odds ratios around 4–11 in favor of CBT-I).

Daytime mood and fatigue also improved.

Depression and fatigue scores were significantly lower in the CBT-I group at 8 weeks, and these differences were largely maintained at 6 months.

This trial is helpful for understanding “mid-intensity” CBT-I options for people with complex health histories:

It shows that self-help CBT-I plus brief nurse support can produce meaningful improvements in sleep and mood in a group with heavy medical and psychiatric burden, not just in relatively healthy older adults.

Limitations:

Even with support, only about 1/3 of veterans reached response, and most still had some insomnia symptoms, which is important for expectations.

The sample was mostly middle-aged or older men, many with prior military-related experiences.

Self-report measures and knowledge that they were receiving a sleep-focused manual may have contributed to part of the observed advantage over health education, even with matched contact time.

For adults 50+ who prefer phone-based coaching and printed materials – or whose local health system can more easily provide nurse support than a sleep psychologist – this study supports nurse-supported self-help CBT-I as a meaningful option.

Section 5 – Study 4: What CBT-I does in the brain (2023 neuroimaging review)

In 2023, Sabot and Baumann reviewed 9 neuroimaging studies that examined people with insomnia before and after CBT-I, using structural MRI and functional MRI (both resting-state and task-based).

Participants in these imaging studies tended to be middle-aged adults, and they give us a window into how CBT-I may change brain function in ways that are relevant across the adult lifespan.

Key findings for sleep-related brain function

Insomnia is linked with “hyperarousal” patterns.

Across studies, people with insomnia showed altered functional connectivity in networks involved in attention, emotion, and self-referential thinking. This included reduced engagement of task-relevant regions and difficulties damping down default mode network activity, consistent with the sense of a “busy mind” in bed.

CBT-I tended to normalize connectivity.

After a course of CBT-I, several studies found that functional connectivity moved closer to patterns seen in good sleepers, with improved regulation of default mode areas and better engagement of frontal regions involved in cognitive control. These changes often paralleled reductions in insomnia severity.

Some structural changes were reported.

A smaller number of studies reported structural MRI changes, such as alterations in grey matter volume or white matter integrity in regions linked to sleep regulation and emotion processing, again tending toward normalization after CBT-I.

This review reinforces a familiar idea: insomnia is not just being bad at sleep – it’s tied to persistent patterns of cognitive and emotional hyperarousal, and CBT-I seems to help the brain unlearn those patterns.

For someone in their 50s, 60s, or 70s, that matters because:

It provides a biological explanation for why changing thoughts, habits, and schedules can have lasting impacts: CBT-I appears to help reset network dynamics in the brain, not just improve how you feel for a few weeks. It supports the observation from long-term trials (like the SHUTi OASIS study) that benefits can persist beyond the active course of treatment.

At the same time, the authors emphasize that these imaging findings are not yet useful for deciding which individual will respond best or for designing custom “brain-targeted” CBT-I prescriptions.

They are best seen as early, encouraging evidence that your brain remains plastic around sleep, even in later life.

Section 6 – Using this evidence: 5 practical steps for CBT-I and your sleep after 50

Based on these four studies – and the broader evidence they sit within – here are 5 ways to use the science of CBT-I in your own decision-making.

1. Decide whether CBT-I fits your situation

CBT-I is most supported when:

Insomnia has lasted 3 months or more, with trouble falling asleep, staying asleep, or waking too early.

You can anchor your wake time and are open to temporarily limiting time in bed to consolidate sleep (sleep restriction).

You’re willing to track sleep with a diary for at least several weeks.

Evidence suggests CBT-I is potentially effective for:

Adults with chronic medical illnesses (cancer, chronic pain, cardiovascular and renal disease, diabetes, stroke, and others)

Older adults 55+ including those in their 70s and 80s, at least when they can use online tools or attend structured programs

People with co-occurring depression and fatigue, where improvements in sleep often help daytime symptoms as well

On the other hand, CBT-I usually needs modification or extra supervision if you have:

Untreated moderate–severe sleep apnea, restless legs/periodic limb movements, or circadian rhythm disorders

Acute mania, psychosis, or very severe untreated depression

Serious cognitive impairment that limits ability to follow instructions

In those situations, clinicians often address the underlying condition and then weave in CBT-I elements as appropriate.

2. Choose a delivery format that matches your life

The studies above show that several formats can work:

Fully digital CBT-I (like SHUTi OASIS in Study 1) – Good if you are comfortable with computers or tablets, like working at your own pace, and want convenient access. Evidence in older adults shows large improvements, high completion rates, and reduced medication use.

Nurse- or coach-supported self-help (Study 3) – A practical option if you prefer phone calls and printed materials, or if mental health specialists are scarce. Expect improvements that are solid but somewhat smaller than full therapist-delivered CBT-I.

Group or individual therapist-delivered CBT-I – Face-to-face CBT-I (individual or group) remains the reference standard in many trials; the 2025 meta-analysis suggests that both individual and group formats are effective across chronic diseases, with longer courses sometimes giving better outcomes.

Practical tips: Ask your primary-care clinician, sleep clinic, or behavioral health provider what CBT-I options they offer – including groups, telehealth, and digital programs embedded in your health system.

3. Set realistic expectations – and a time frame

Across trials:

Many people see noticeable improvement within 2–4 weeks, but the full CBT-I course often lasts 6–8 weeks (or up to 9–10 weeks in digital programs).

Typical results for those who engage reasonably well include:

ISI score drops of 6–9 points (large improvements in severity)

Shorter time to fall asleep, fewer and shorter awakenings, higher sleep efficiency

Modest changes in total sleep time (for example, ~24–46 minutes in the SHUTi OASIS trial, across conditions)

Realistic expectations:

Remission rates vary by setting and population (for example, 30% at 8 weeks in the VA trial; nearly half at 1 year in SHUTi OASIS; ~54% vs ~18% pooled remission in the chronic disease meta-analysis).

Plan for a temporary dip in energy during early sleep restriction weeks. This is common but it’s important to coordinate with your clinician if you have complex medical conditions.

A helpful mindset is to treat CBT-I as a training block for your brain and body, where a few weeks of focused effort can produce benefits that extend into later life.

4. Integrate CBT-I with your health conditions and medications

For adults 50+ with chronic disease, CBT-I is rarely used in isolation:

Bring your full medication list (especially sedatives, antidepressants, and “PM” pain relievers or antihistamines) to any clinician helping with CBT-I. Changes in your sleep schedule can interact with these drugs.

CBT-I can support gradual reductions in sleep medications, as seen in the SHUTi OASIS trial where older adults using digital CBT-I reduced medicated nights more than those receiving education. Any change in dose, however small, should be planned with your prescribing clinician.

If pain, breathlessness, urinary frequency, or other nighttime symptoms are prominent, it often helps to stabilize those symptoms as much as possible while you work through CBT-I, so that treatment targets can be more clearly defined.

Because CBT-I typically asks you to get out of bed when you are awake, adults with fall risk (orthostatic hypotension, neuropathy, sedating medications) may need extra planning: good lighting, assistive devices, safe walking paths, and possibly modified instructions.

5. Plan for maintenance and setbacks

The longer-term follow-ups in SHUTi OASIS and many trials in the 2025 meta-analysis show that gains can last months to a year or longer, especially when people keep using the skills they learned.

Helpful maintenance strategies:

Keep a short “check-in” sleep diary for a week every few months, or when you notice insomnia creeping back.

Re-apply the core tools (consistent wake time, stimulus control, temporary tightening of time in bed) for a few weeks when symptoms flare.

Consider a booster session or a refresher digital module once or twice a year, particularly after big life changes.

If you used a nurse-supported or therapy-based program, ask whether follow-up or group refreshers are available.

Setbacks can mean old patterns re-appeared under new stress, and your sleep physiology may need another gentle nudge back toward the healthier patterns you already practiced.

For many adults over 50, insomnia has been a long-term companion – part of the background of caregiving, career stress, and chronic illness.

The studies reviewed here show that CBT-I can reshape sleep in later life, whether delivered digitally, in groups, or with brief nurse support; that it appears safe across a wide range of chronic conditions; and that it exerts its effects not only on behavior and mood but also on the networks of the brain that keep you on high alert at night.

The trade-offs are: CBT-I asks for motivation, consistency, and a willingness to tolerate some short-term discomfort. Not everyone reaches full remission, and access is still uneven. But the evidence suggests that your sleep remains modifiable, even after decades of poor nights, and that investing effort in CBT-I can pay dividends in energy, mood, and resilience for the years ahead.

If insomnia has been persistent, this might be a good time to talk with your clinician about which CBT-I path – digital, group, individual, or nurse-supported – fits your health, your preferences, and your life right now.

—Kat

P.S. If you’ve tried CBT-I and it hasn’t worked (or you’re not sure it’s right for you), I help people figure out what’s going on with their sleep.

References

Scott AJ, Correa AB, Bisby MA, et al. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia in People With Chronic Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2025;185(11):1350–1361. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2025.4610. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2025.4610

Ritterband, L.M., Shaffer, K.M., Thorndike, F.P. et al. A randomized controlled trial of a digital cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia for older adults. npj Digit. Med. 8, 458 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-01847-0

Ulmer CS, Voils CI, Jeffreys AS, et al. Nurse-Supported Self-Directed Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2024;184(11):1356–1364. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2024.4419. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2024.4419

Sabot D, Baumann O. Neuroimaging Correlates of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia (CBT-I): A Systematic Literature Review. J Cogn Psychother. 2023 Feb 1;37(1):82-101. doi: 10.1891/JCPSY-D-21-00006. Epub 2022 Jun 3. PMID: 36787999. https://doi.org/10.1891/JCPSY-D-21-00006