Does "deep sleep" clear Alzheimer's proteins?

New human data (Oct 2025) shows "time in deep sleep" predicted 0% of amyloid removal—here’s what does:

Each night, a remarkable waste clearance process takes place within the brain.

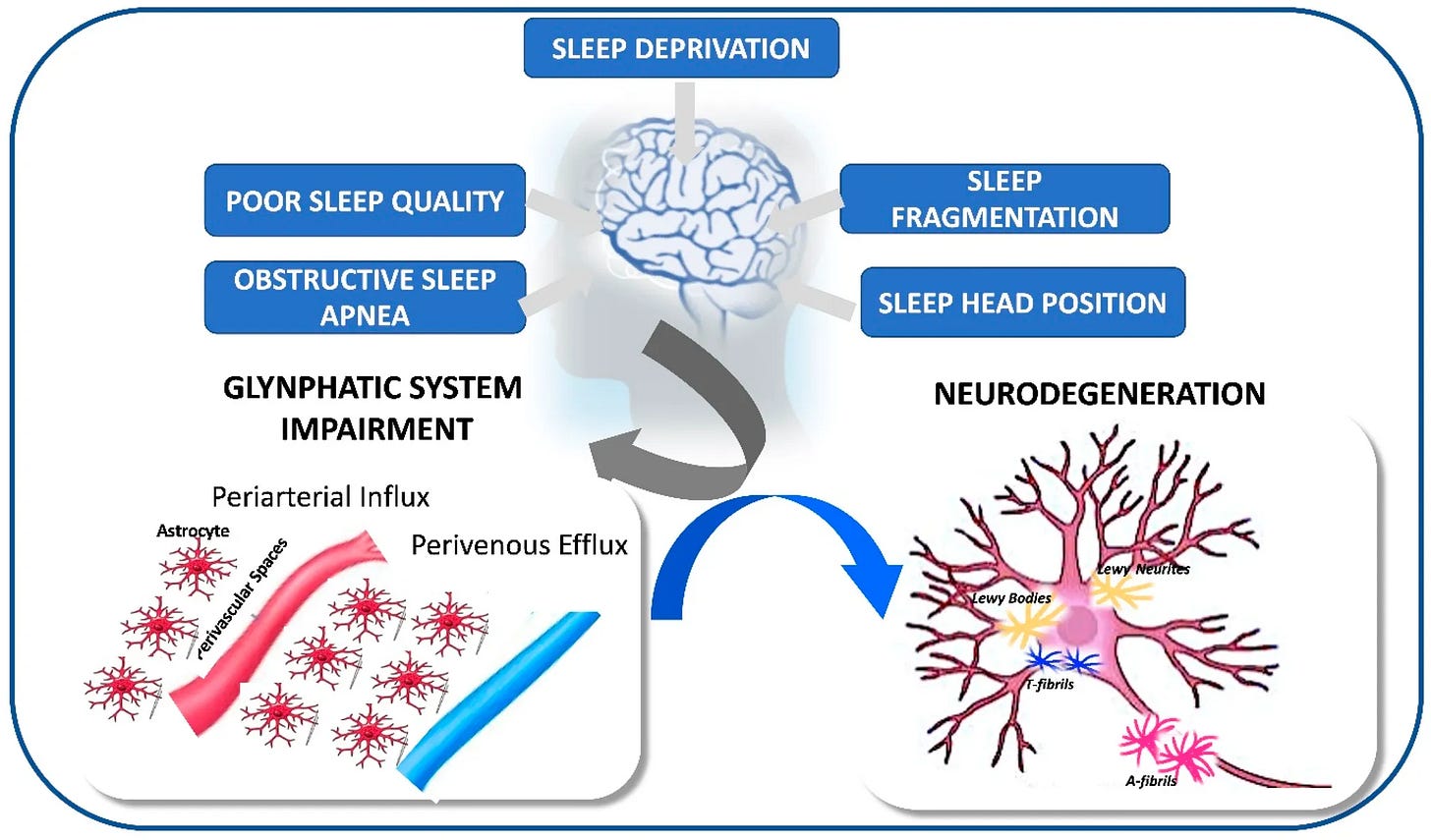

This is the glymphatic system, a recently discovered network that uses cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) to flush out neurotoxic proteins—specifically amyloid-β (Aβ) and tau, the hallmark proteins linked to Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s pathology—that accumulate during our waking hours. This system, in turn, drains into the body’s lymphatic vessels for processing and safe removal from the body.

Though this “brain-washing” system was formally described in 2012, for the decade that followed, our understanding was built predominantly on animal models. This animal research was critical, as it established the high-stakes link between glymphatic impairment and neurodegeneration.

Yet a critical question remained: how much of this translates to humans & under what specific sleep conditions?

Earlier work told us that glymphatic activity was strongest in slow-wave (deep) sleep. The general thought was that if we entered the stage, the brain cleaning process turned on.

However, the latest evidence now challenge that understanding.

Specifically, human data just published in October 2025 shows that simply spending time in “deep sleep” or “N2/N3” stage sleep is not enough to ensure optimal clearance of toxic amyloid-β and tau proteins from the brain

So, what kind of sleep actually clears these toxic proteins most effectively?

This article explores what the latest human data reveals. We’ll examine:

The links between glymphatic activity and neurodegenerative markers, and how this is impacted by the ‘quality’ vs. the ‘hours’ (duration) of deep sleep.

Whether the brain produces more toxic proteins during poor sleep, clears them less efficiently, or both

The specific sleep disruptions that impair glymphatic function and therefore impair brain waste clearance

Finally, we will examine:

How to support the non-negotiable foundation of glymphatic function in midlife and beyond

Let’s dive in.

Section 2. What Recent Human Evidence Show About Sleep-Driven Brain Waste Clearance In Healthy Mid-Life Adults—The Glymphatic Function (2024-2025)

Is getting enough hours of deep sleep—such as that measured by a consumer wearable—sufficient to ensure our brain is optimally clearing the toxic proteins linked to Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s?

This is the question for anyone tracking their sleep stages via a wearable device.

While the idea that “deep sleep cleans the brain” is well-established, a landmark 2025 study (Dagum et al., October 2025 preprint) involving researchers from Stanford and the University of Washington School of Medicine has revealed an important nuance

Conducted in healthy midlife adults aged 49–66, this study shows:

The brain’s ability to clear neurotoxic proteins (amyloid-β & tau) depends on sleep “neurophysiological quality” (signals that show how intensely the brain is engaged in the sleep state—which I describe below), not just the duration of the sleep stage (time spent in N2+N3 stages).

Simply put, it is not enough to just enter “Deep Sleep” (Stage N2/N3).

Nor is it enough to log a certain number of hours in N2/N3.

So, if the ‘N2/N3’ sleep stage label is insufficient, how did the researchers define & quantify this sleep “neurophysiological quality”?

In addition to the sleep stage, the researchers tracked these 4 metrics in healthy adults that described the moment-to-moment neurophysiological state of the brain during sleep:

EEG Delta Power: The electrical strength and synchronization of slow brain waves

Vascular Pulsatility & Compliance: How flexible and responsive blood vessels are (facilitating CSF fluid flow).

Heart Rate Variability (HRV): The balance of the autonomic nervous system (lower sympathetic tone)

Parenchymal Resistance: How easily fluid (CSF) can move through the brain tissue

Together, these signals formed the sleep ‘neurophysiological quality’ index that the researchers compared against N2/N3 duration for predicting protein clearance.

How Did These 4 Metrics of Sleep “Neurophysiological Quality” Compare with Sleep Stage Duration For Amyloid-β & Tau Protein Removal?

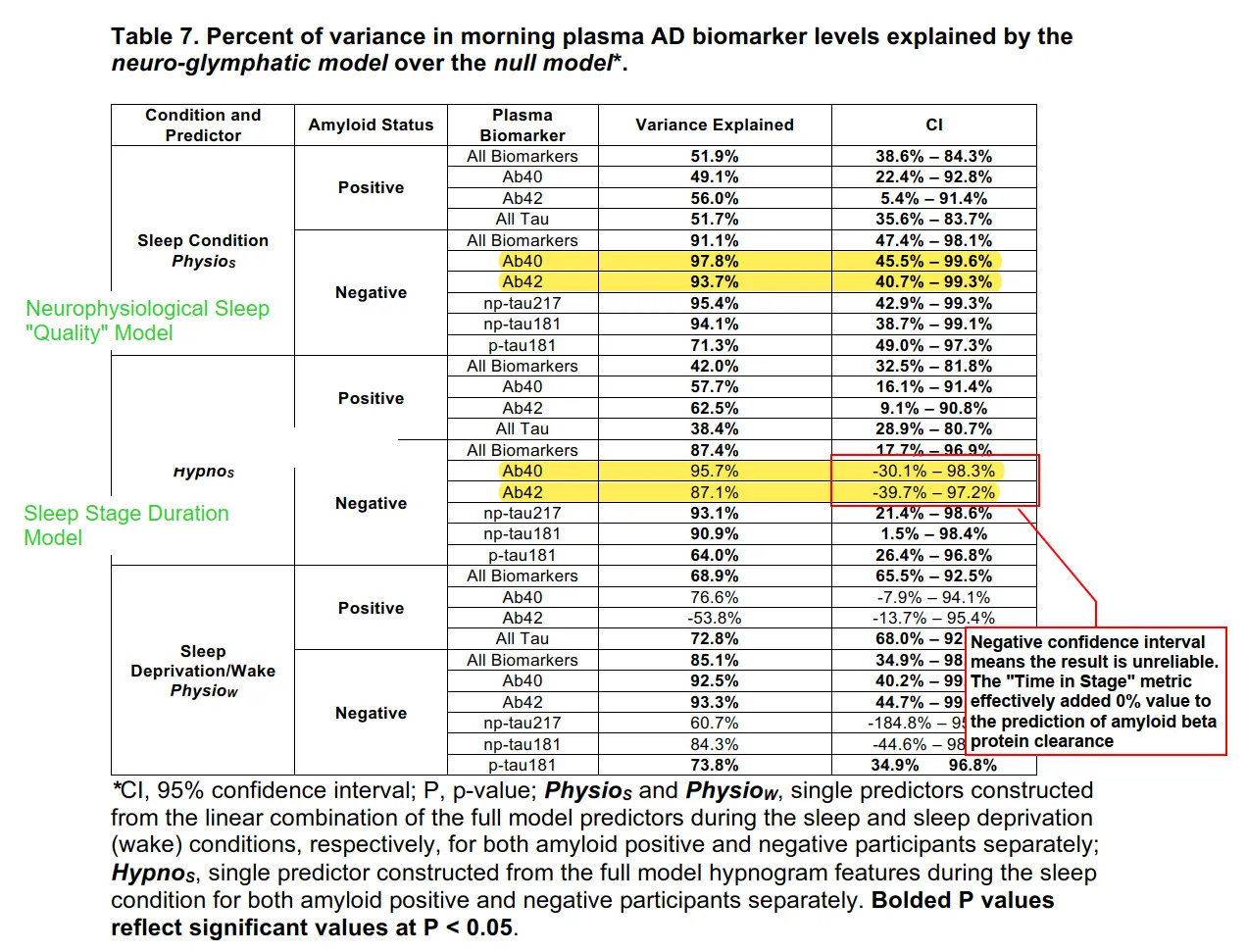

The researchers then tested how much of the overnight change in removal of these proteins from the brain could be explained by two models: one based on time in each sleep stage (N1, N2+N3, REM), and one based on the neurophysiological quality.

They found a difference in the 2 major neurotoxic protein classes amyloid-β & Tau:

1. For Tau (The Tangle Protein, np-tau181 and p-tau181)

Tau appears to be the “easier” protein to remove. Both time spent asleep and sleep quality accounted for a meaningful portion of its overnight change.

Sleep Stage Duration: Simply spending time in NREM (N2+N3) sleep accounted for 64%-93% of the overnight change in tau levels.

Neurophysiological Quality: The neurophysiological markers accounted for 71%-95% of the overnight change.

Standard, lighter NREM sleep appears sufficient to support tau removal.

2. For Amyloid-β (The Plaque Protein, Aβ40 and Aβ42)

Amyloid-β—the primary driver of Alzheimer’s plaques—behaved differently.

Neurophysiological Quality: The quality markers — particularly low parenchymal resistance paired with strong delta power — accounted for 94%-98% of the overnight change.

Sleep Stage Duration: The time spent in Deep Sleep (N3) did not perform better than the statistical baseline (a prediction based on the participant’s evening levels). In the data, this metric had a confidence interval of -30.1% to 98.3%. Because this range includes negative numbers, the result is indistinguishable from 0; this is interpreted to mean that sleep stage duration effectively accounted for 0% of the change in amyloid removal.

0%. In other words, knowing how many minutes a participant spent in deep sleep offered no predictive value (0%) regarding how much Alzheimer’s plaques they cleared.

The Takeaway

So, while lighter NREM sleep can facilitate tau protein clearance, clearing amyloid-β effectively requires the brain to enter a higher-quality neurophysiological state during deep NREM sleep.

This finding reframes the sleep-and-brain-health discussions:

It is not the stage name that protects the brain, but the quality, strength and continuity of the NREM neurophysiology occurring within it.

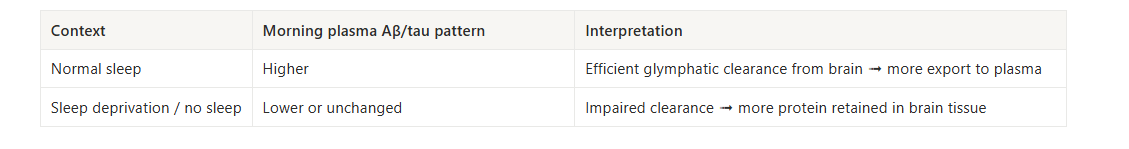

Dagum’s team also contrasted normal sleep with total sleep loss.

On a night or normal sleep, once the brain enters this high-quality NREM state, it shifts into a clearance-dominant mode: production of amyloid-β and tau slows, and the glymphatic system pushes more of what accumulated during the day out into the bloodstream. On a sleep-deprived night, the brain did not make that shift.

Production of these proteins remains closer to its waking pattern, and

the strong glymphatic clearance was impaired.

This is why a lower or unchanged morning blood level after poor sleep likely means more amyloid-β and tau stayed in brain tissue, not that less was produced.

With this in mind, we can now ask how aging changes this picture.

Section 3. Does Aging affect Glymphatic Function?—Why Sleep “Quality” Matters Even More After 50

As we move into our 50s and beyond, the glymphatic system is working with different “hardware” than it had at 20 or 30. The pipes are still there, but they are not as efficient as they once were. Arteries tend to stiffen, the perivascular channels that guide fluid can narrow, and the small water channels (AQP4) on astrocytes become less precisely organized.

These changes make it harder for the brain to move waste fluid as freely as it once did.

Admittedly, we cannot fully reverse those age-related structural shifts in the generally healthy adult.

Yet, this is why the nightly state that drives the glymphatic function—deep, continuous NREM sleep with strong neurophysiologic depth—matters more after 50.

The silver lining is this: We can modify and improve—every night—the state that drives the system: deep, continuous NREM sleep with favorable glymphatic mechanics.

The challenge of course is we do not have a home device that can show the kind of multi-signal brain and vascular metrics used in research labs to signal “sleep quality.” Consumer sleep trackers that report “N2/N3 minutes” also give us, at best, an incomplete picture: they cannot tell us whether those minutes reached the depth that matters for glymphatic activity.

So: how do we know whether our NREM quality is sufficient or impaired in ways that affect glymphatic clearance?

We do it indirectly—by looking at sleep disruption patterns that are known to impair deep NREM stability, continuity, or circadian alignment.

5 Sleep Disruptions Patterns That Can Impair Glymphatic Clearance (& Aβ/Tau Clearance Capacity)

Fragmented sleep (frequent brief arousals): Breaks deep NREM into shorter bouts before clearance mechanisms reach full capacity

Chronic short duration(<6 hours): Compresses the window when waste transport operates at peak efficiency

NREM-poor architecture (suppressed slow-wave sleep despite adequate total hours): Limits the sleep stage where clearance is most active

Circadian misalignment (adults with advanced, irregular or delayed schedules): Decouples sleep from hormonal and vascular rhythms that support clearance

Unrefreshing sleep (waking tired despite good duration and tracker scores): Suggests insufficient restorative depth that consumer devices cannot detect

All these patterns point to the same foundation: the brain depends on consolidated, high-quality NREM sleep for optimal glymphatic function.

So how do we support it?

Section 4. What Affects Sleep Depth in Midlife and Beyond—And How to Support It

First, a note on what doesn’t help: sedative use (agents that blunt slow-wave activity, such as some Z-drugs and benzodiazepines) presents a conflict of interest for the aging brain. While these agents help you lose consciousness, they degrade natural NREM architecture, rendering sleep unfavorable for glymphatic clearance.

Second, let’s acknowledge your baseline:

If you’re still reading this, you’re likely among the small percentage of health-conscious, informed individuals who’ve optimized the fundamentals. Light. Caffeine. Magnesium, etc.

The frontier for sophisticated sleep optimization in midlife and advanced age requires a shift from external environment to internal terrain.

From Hormone Levels to Hormonal Function

In Sections 2 and 3, we saw that glymphatic clearance depends less on stage labels and more on the depth and continuity of NREM sleep.

In midlife, hormone function is one of the key internal drivers that support that NREM depth and continuity,

Optimal hormone function—determined by balanced production, efficient transport, effective receptor use, and proper clearance—is essential for slow-wave sleep.

It is not merely a matter of “topping up” declining levels. Hormonal impact on sleep follows a “Goldilocks principle”: both deficiency and excess disrupt NREM architecture.

Furthermore, if hormones are produced but poorly transported, inefficiently utilized, or poorly cleared, adequate hormone levels still do not translate into optimal functional hormonal action—potentially resulting in either effective deficiency or excess that undermines intended biological function.

In midlife and advanced age, supporting optimal hormone function therefore benefits from targeted & deliberate effort rather than reliance on the robust dynamics of earlier decades.

Here’s How Testosterone, Progesterone, and Estrogen Affect the Sleep Depth Required for Glymphatic Clearance:

Testosterone → NREM Depth and Stability

The Function: Testosterone supports slow-wave sleep when levels are physiologic, but destabilizes it when levels are too low or too high.

The Mechanism: Normal physiologic testosterone promotes deeper NREM through its effects on muscle repair, thermoregulation, and GABAergic tone. In contrast, both low testosterone (common in aging) and pharmacologic-level testosterone (common in overshooting HRT) can fragment deep sleep. Low levels reduce sleep drive and increase nighttime awakenings.

The Nuance: Excess levels raise metabolic rate and sympathetic activation, which reduces slow-wave consolidation. Excess testosterone can also convert to estrogen via aromatization in men when this pathway is poorly regulated and/or when estrogen is poorly cleared.

Net effect: Testosterone has a U-shaped relationship with sleep. Mid-range levels support deeper sleep; both extremes undermine it.

Progesterone → GABAergic Support for Slow-Wave Sleep

The Function: Progesterone directly promotes NREM sleep through its GABA-enhancing metabolites.

The Mechanism: This is the hormone with the clearest mechanistic connection to deep sleep. Progesterone’s neuroactive metabolites (especially allopregnanolone) increase GABAergic inhibitory tone—the system that stabilizes stage N3 and prevents premature REM intrusion.

The Nuance: When progesterone declines, the loss of this natural sedative support creates lighter, more easily disrupted slow-wave sleep. It is often the first domino to fall in perimenopausal sleep disruption.

Net effect: Progesterone decline is one of the more underappreciated reasons deep sleep degrades in midlife.

Estrogen → Temperature and Sleep Architecture

The Function: Estrogen influences slow-wave sleep mainly through temperature regulation and serotonin pathways.

The Mechanism: Adequate estrogen helps stabilize sleep cycles and increases slow-wave continuity by narrowing the core-temperature curve and supporting the conversion of serotonin to melatonin. When estrogen is low, slow-wave sleep shortens and becomes fragile.

The Nuance: However, excess or poorly cleared estrogen (a state of being “high for the tissue”) is equally disruptive. If clearance is impaired in women, or if there is excess aromatization (and/or poor clearance—- in men) the resulting estrogen dominance causes thermoregulatory instability and heightened nighttime arousal.

Net effect: Estrogen keeps sleep architecture organized. Too little or poorly cleared estrogen destabilizes the N3/REM sequence.

Glymphatic function depends on NREM quality, and NREM quality is profoundly shaped by hormone function in midlife and beyond.

Because these hormones affect both men & women, you can learn more about my most popular and comprehensive self-paced digital program, the Trio Hormone Sleep Improvement Solution.

It guides you to optimize and support your hormone function through the full physiological pathway—from production and transport to utilization and clearance—without prescriptions, supplements, or pharmaceuticals.

Sleep is Not Passive Rest—It is Active Neuroprotection

For decades, I viewed sleep as a passive non-necessity—a time to recharge. If I had known early on that deep NREM sleep was in fact, a high-energy, active defense against neurodegeneration, I would not have waited as long as I did to become serious about fixing my sleep.

Quality NREM sleep is the engine that clears unwanted metabolites and neurotoxic proteins from the brain. In midlife and beyond, keeping that engine running well requires more than good external hygiene.

It requires deliberate & targeted support of the internal systems that stabilize and sustain high-quality NREM.

And, while we can’t measure glymphatic flow at home, we can feel its effects. That mental clarity, emotional steadiness, and cognitive sharpness we feel after great sleep are not just mood boosts—they are the real-time biofeedback that good things happened in the brain overnight.

By supporting the hormonal signals that stabilize and sustain deep NREM sleep, you are doing more than just resting. You are making a compounded investment in your future cognitive independence, protecting your ability to engage with the world sharply and fully for decades to come

Warmly,

—Kat

P.S. If your sleep has changed since midlife—lighter, shorter, or more fragile under stress—habits alone are not enough. The midlife hormonal transition often shifts how your body builds and maintains NREM depth, but that function can be supported at any age.

Sleep OS: Hormones was designed for this stage. It offers a self-paced, step-by-step process to strengthen hormonal pathways that stabilize sleep—without hormone therapy or lab testing.

👉 You can learn more about my most popular program, the Trio Hormone Sleep Improvement Solution, here:

👉 Or, explore the foundational Sleep & Stress Sleep Solution here:

References

Robbins R, Weaver MD, Sullivan JP, Quan SF, Gilmore K, Shaw S, Benz A, Qadri S, Barger LK, Czeisler CA, Duffy JF. Accuracy of Three Commercial Wearable Devices for Sleep Tracking in Healthy Adults. Sensors (Basel). 2024 Oct 10;24(20):6532.

Dagum, P., Elbert, D. L., Giovangrandi, L., Singh, T., Venkatesh, V. V., Corbellini, A., Kaplan, R. M., Rane Levendovszky, S., Ludington, E., Yarasheski, K., Lowenkron, J., VandeWeerd, C., Lim, M. M., & Iliff, J. J. (2025). The glymphatic system clears amyloid beta and tau from brain to plasma in humans. medRxiv.

Ma, J., Chen, M., Liu, GH. et al. Effects of sleep on the glymphatic functioning and multimodal human brain network affecting memory in older adults. Mol Psychiatry 30, 1717–1729 (2025).

Vinje V, Zapf B, Ringstad G, Eide PK, Rognes ME, Mardal KA. Human brain solute transport quantified by glymphatic MRI-informed biophysics during sleep and sleep deprivation. Fluids Barriers CNS. 2023 Aug 18;20(1):62.

Yoon JE, Ji M, Hwang I, Lee WJ, Yu S, Kim J, Lee C, Lee H, Koh B, Bae H, Yun CH. Brain water dynamics across sleep stages measured by near-infrared spectroscopy: Implications for glymphatic function. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2025 Nov;45(11):2203-2216.

Ding Z, Fan X, Zhang Y, Yao M, Wang G, Dong Y, Liu J, Song W. The glymphatic system: a new perspective on brain diseases. Front Aging Neurosci. 2023 Jun 15;15:1179988.

Hauglund NL, Andersen M, Tokarska K, Radovanovic T, Kjaerby C, Sørensen FL, Bojarowska Z, Untiet V, Ballestero SB, Kolmos MG, Weikop P, Hirase H, Nedergaard M. Norepinephrine-mediated slow vasomotion drives glymphatic clearance during sleep. Cell. 2025 Feb 6;188(3):606-622.e17.

He, Z., Sun, J. Clearance mechanisms of the glymphatic/lymphatic system in the brain: new therapeutic perspectives for cognitive impairment. Cogn Neurodyn 19, 111 (2025).

Ferini-Strambi, L.; Salsone, M. “Glymphatic” Neurodegeneration: Is Sleep the Missing Key? Clin. Transl. Neurosci. 2024, 8, 23.

Shirolapov, I.V., Zakharov, A.V., Smirnova, D.A. et al. The Role of the Glymphatic Clearance System in the Mechanisms of the Interactions of the Sleep–Waking Cycle and the Development of Neurodegenerative Processes. Neurosci Behav Physi 54, 199–204 (2024).

Yoon JE, Ji M, Hwang I, Lee WJ, Yu S, Kim J, Lee C, Lee H, Koh B, Bae H, Yun CH. Brain water dynamics across sleep stages measured by near-infrared spectroscopy: Implications for glymphatic function. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2025 Nov;45(11):2203-2216.

Barrett-Connor E, Dam TT, Stone K, Harrison SL, Redline S, Orwoll E; Osteoporotic Fractures in Men Study Group. The association of testosterone levels with overall sleep quality, sleep architecture, and sleep-disordered breathing. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008 Jul;93(7):2602-9.

Begemann, K., Rawashdeh, O., Olejniczak, I. et al. Endocrine regulation of circadian rhythms. npj Biol Timing Sleep 2, 10 (2025).

Lord C, Sekerovic Z, Carrier J. Sleep regulation and sex hormones exposure in men and women across adulthood. Pathol Biol (Paris). 2014 Oct;62(5):302-10.

Peter Y. Liu, Brendon Yee, Susan M. Wishart, Mark Jimenez, Dae Gun Jung, Ronald R. Grunstein, David J. Handelsman, The Short-Term Effects of High-Dose Testosterone on Sleep, Breathing, and Function in Older Men, The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, Volume 88, Issue 8, 1 August 2003, Pages 3605–3613

Hernández-Pérez JG, Taha S, Torres-Sánchez LE, Villasante-Tezanos A, Milani SA, Baillargeon J, Canfield S, Lopez DS. Association of sleep duration and quality with serum testosterone concentrations among men and women: NHANES 2011-2016. Andrology. 2024 Mar;12(3):518-526.

Lord C, Sekerovic Z, Carrier J. Sleep regulation and sex hormones exposure in men and women across adulthood. Pathol Biol (Paris). 2014 Oct;62(5):302-10.

Peter Y. Liu, Brendon Yee, Susan M. Wishart, Mark Jimenez, Dae Gun Jung, Ronald R. Grunstein, David J. Handelsman, The Short-Term Effects of High-Dose Testosterone on Sleep, Breathing, and Function in Older Men, The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, Volume 88, Issue 8, 1 August 2003, Pages 3605–3613

Hernández-Pérez JG, Taha S, Torres-Sánchez LE, Villasante-Tezanos A, Milani SA, Baillargeon J, Canfield S, Lopez DS. Association of sleep duration and quality with serum testosterone concentrations among men and women: NHANES 2011-2016. Andrology. 2024 Mar;12(3):518-526.

Dorsey A, de Lecea L, Jennings KJ. Neurobiological and Hormonal Mechanisms Regulating Women’s Sleep. Front Neurosci. 2021 Jan 14;14:625397.

Empson, J. A. C., & Purdie, D. W. (1999). Effects of sex steroids on sleep. Annals of Medicine, 31(2), 141–145.

Gava G, Orsili I, Alvisi S, Mancini I, Seracchioli R, Meriggiola MC. Cognition, Mood and Sleep in Menopausal Transition: The Role of Menopause Hormone Therapy. Medicina (Kaunas). 2019 Oct 1;55(10):668.

Annika Haufe, Brigitte Leeners, Sleep Disturbances Across a Woman’s Lifespan: What Is the Role of Reproductive Hormones?, Journal of the Endocrine Society, Volume 7, Issue 5, May 2023, bvad036

Anne Caufriez, Rachel Leproult, Mireille L’Hermite-Balériaux, Myriam Kerkhofs, Georges Copinschi, Progesterone Prevents Sleep Disturbances and Modulates GH, TSH, and Melatonin Secretion in Postmenopausal Women, The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, Volume 96, Issue 4, 1 April 2011, Pages E614–E623

Friess E, Tagaya H, Trachsel L, Holsboer F, Rupprecht R. Progesterone-induced changes in sleep in male subjects. Am J Physiol. 1997 May;272(5 Pt 1):E885-91.