Eggs & longevity: what most advice miss

For decades I ate 3 eggs/day—now I eat 3 eggs a year. Here’s why:

Are eggs a longevity food?

I’ve been optimizing my health for ~20 years—refining everything from sleep, to nutrients, training, gut health, inflammation and lipids.

And, for much of that time, I ate 3 eggs daily.

Now?

I eat about 3 a year.

The reason isn’t what you might expect.

It’s not about cholesterol.

Nor is it about fat.

It has to do with how:

I’ve kept inflammation consistently low—my hs-CRP stays at minimum detectable level ~0.1 mg/L—and

how I keep my LDL-C in the 70s mg/dL.

Here are 3 factors that changed how I think about eggs & longevity:

Factor 1: Egg “Immunogenicity” & Inflammation Control

Let’s explain why inflammation & immunogenicity is important.

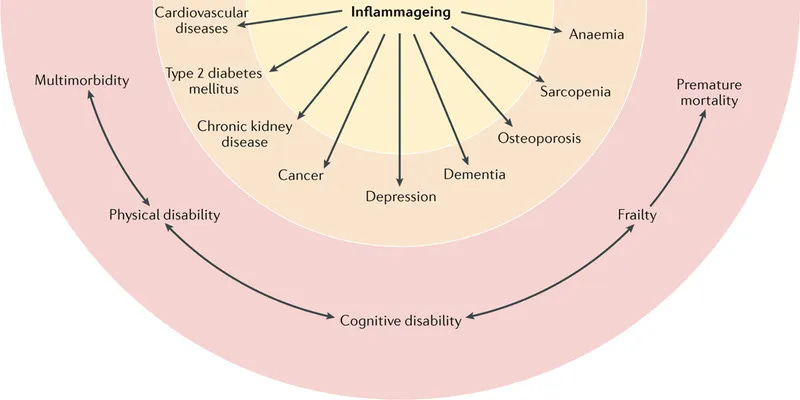

Chronic low-grade inflammation is linked to accelerated aging across multiple systems.

And, what is “immunogenicity?”

Immunogenicity is to the tendency of a substance to trigger an immune response that can contribute to low-grade inflammation—even a subtle one without obvious symptoms

In research, individuals with elevated inflammatory markers show

faster vascular aging;

increased cardiovascular risk and higher mortality.

Keeping inflammation minimized—particularly markers like hs-CRP (high-sensitivity C-reactive protein)—is one lever for maintaining function over decades.

Eggs, particularly egg whites, contain proteins that potentially provoke immune responses in some individuals.

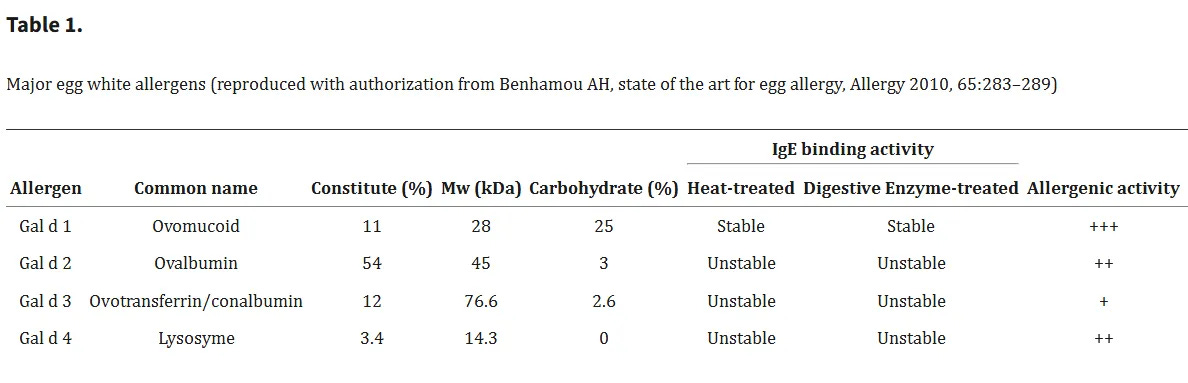

The primary proteins involved are ovalbumin, ovomucoid, and ovotransferrin.

These are well-documented allergens, but immune reactivity doesn’t require classic allergic responses like hives or anaphylaxis. Generally speaking (and in my own experience), low-grade immune activation can occur without obvious signals—little/no digestive upset, no skin reactions, no acute discomfort.

This matters because even subtle immune engagement adds to cumulative inflammatory load.

Your immune system allocates resources to respond to these proteins, and that response—however mild—adds to the workload required to manage actual threats like damaged cells, pathogens, or oxidative stress. Over time, repeated exposures can contribute to the chronic low-grade inflammation pattern that many longevity-focused individuals work to avoid.

For me, removing eggs was a strategic decision to eliminate an avoidable immune trigger.

I don’t have a diagnosed egg allergy, but I observed that my inflammatory markers improved when I reduced egg intake, and they’ve remained consistently low since I adopted a low-inflammation lifestyle 6 year ago.

This is an underappreciated factor in the “eggs or no eggs” consideration—immunogenicity may be relevant for some people, particularly those with unrecognized sensitivity, even in the absence of obvious reactivity.

If you have very low hs-CRP, no signs of immune sensitivity, and tolerate eggs well, this factor may not be relevant to you.

But if you’re working to maintain low inflammation as part of a longevity strategy, egg immunogenicity is worth being mindful of.

By the way: Inflammation and sleep are bidirectionally linked. Inflammatory signaling can fragment sleep and reduce sleep efficiency, with stage-specific effects on slow-wave and REM sleep varying across studies. This creates a feedback loop: poorer sleep raises inflammation, which further impairs recovery and may accelerate biological aging.

Factor 2: Cholesterol & Saturated Fat—Secondary but Aligned

Immunogenicity drives my decision regarding eggs, but 2 additional factors support this choice: dietary cholesterol and saturated fat.

These considerations don’t lead—they reinforce.

I prefer lower dietary cholesterol intake because my lipid profile appears sensitive to dietary input. This is individual variability—some people show minimal lipid response to dietary cholesterol, while others show meaningful increases in LDL-C or ApoB. I fall into the latter category, and managing dietary cholesterol is one component of maintaining my LDL-C within target range.

A common misconception: you need to eat cholesterol to have cholesterol.

That’s not accurate.

Our liver and other cells synthesize cholesterol de novo—meaning “from scratch”—from acetyl-CoA, a molecule derived from the breakdown of carbohydrates, fats, and proteins.

In other words, as long as you’re consuming adequate food and energy, our body makes the cholesterol it needs internally.

This body’s own internal production supplies what our body needs for hormone synthesis, membrane structure, and cellular function.

Dietary cholesterol therefore, is not essential. For individuals whose lipids respond to dietary intake, minimizing cholesterol from food can support tighter lipid control.

Eggs also contain saturated fat— about 1.6 g in the yolk and about 3.2 g in a whole large egg. I prefer a lower saturated-fat approach based on how my lipids respond.

This isn’t a universal recommendation.

It’s a relevant consideration for individuals whose LDL-C or ApoB levels are high despite a mindful lifestyle and/or appear sensitive to saturated fat intake.

If You Want to See How I Lowered My LDL-C by ~50% in 2021 & How I fixed An Unexpected Uptick in May 2025 Without Medication:

You might be interested in these Vault Insiders Exclusive articles :

Factor 3: What You Might Be Missing When You Don’t Eat a Food

Now, when you’re not eating a particular food/food group regularly, a critical next step is to think about:

what nutrients that food (uniquely) delivered

whether you’re getting them elsewhere, and

if not, how you can do that

In the case of eggs, the primary nutrient to consider is choline.

Eggs are one of the most concentrated food sources—a single large egg contains approximately 150 milligrams, primarily as phosphatidylcholine in the yolk. Choline supports multiple physiological functions, including acetylcholine synthesis, phospholipid membrane structure, and methyl group donation for one-carbon metabolism.

Other foods contain choline—beef liver, salmon, legumes—but eggs deliver it in higher concentration with less total food volume. Lentils, for example, contain choline, but you’d need to consume several cups daily to approach the choline content of 2 to 3 eggs. For many individuals, that’s not particularly practical (though not impossible) on a daily basis.

This is where supplementation might be practical.

At the time of writing, I’m not able to say whether choline from eggs is more bioavailable than choline from supplements. And, bioavailability may differ across supplement forms (CDP-choline, alpha-GPC, or choline bitartrate).

But, even if eggs showed better bioavailability, I would still choose supplementation given the immunogenic consideration I’m working to minimize, and, on the basis of a ‘first principles’ consideration, its simply easier to ‘add’ than to remove something from your body.

My Approach to Eggs & Choline

I take very few supplements, but choline is one of them because the immunogenicity consideration makes it worth it for me.

If eggs work well for you, your inflammatory markers are where you want them, and you don’t notice any reactivity, eggs can serve as a practical (& tasty) choline source.

If you’re uncertain about tolerance—or if you experience low grade non specific signs (brain fog, unexplained low energy, joint aches, etc.), or minimizing immune activation is a priority in your longevity strategy—supplemental choline or other food sources of choline might be a path to consider.

Conclusion — What This Means for Longevity

In longevity, foods fall into three categories: protective, neutral, possibly negative/negative.

Protective foods lower inflammation and strengthen repair systems.

Neutral foods neither help nor harm.

Possibly negative/negative foods introduce immune or metabolic signals that raise background stress over time.

Eggs fall into that last group for me.

They’re nutrient-dense but their potential immunogenic and lipid effects can work against the stability I aim to maintain. When hs-CRP stays near 0.1 mg/L and LDL-C in the 60-70s, the margin for unnecessary activation is small—and worth supporting.

Inflammation defines that hierarchy.

What protects the system over decades matters more than what looks nutrient-rich on paper.

And, the goal is not restriction—but selectivity.

The Longevity Vault Approach: Helping You Personalize Your Own Strategy & Minimizing Unnecessary Immune Activation—Where Eggs Fit For You

Keeping chronic inflammation low is one of the highest-leverage longevity strategies.

Every avoidable immune trigger you remove creates capacity for your immune system to manage actual threats—pathogens, damaged cells, oxidative stress.

The encouraging part is that an anti-inflammatory lifestyle is highly actionable.

In individuals I work with, I have seen inflammation decline within weeks once major triggers are removed and recovery pathways—sleep, nutrient status, and gut balance—are supported.

The body is remarkably responsive when the inflammatory load is reduced.

Eggs represent one decision point in that larger ‘low-inflammation’ lifestyle framework.

For me, the immunogenicity consideration outweighs the nutrient benefits eggs provide. Choline supplementation (& eating lentils) solves the replacement question without the immune exposure (and for those with a healthy digestive system, lentils are potently anti-inflammatory). Cholesterol and saturated fat support this decision.

Your situation may differ.

You may have very low inflammatory markers despite eating eggs, and use them as an efficient choline source.

The question isn’t whether eggs (or any food) are “good” or “bad”—it’s whether they align with your biology, your inflammatory baseline, and your longevity priorities.

The Longevity Vault framework is built around that exact principle—using data and observation to personalize choices.

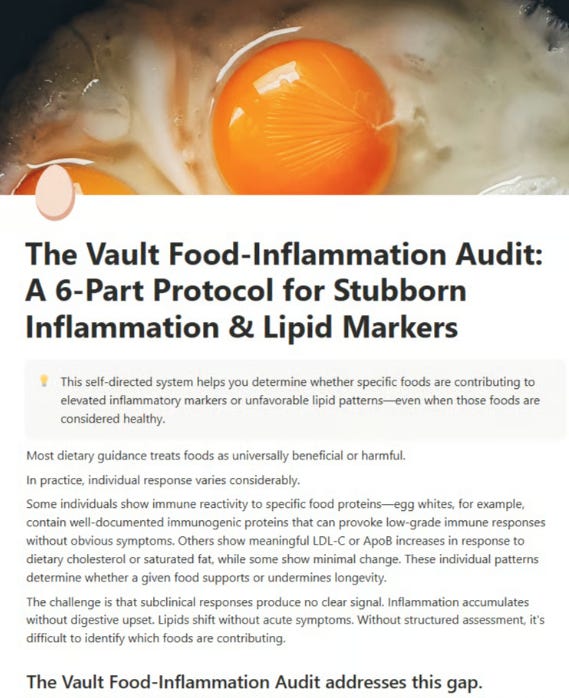

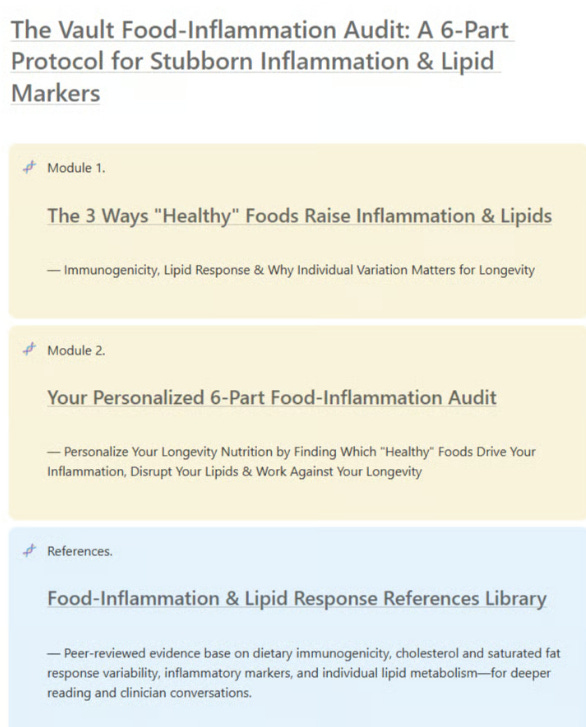

You can use the resource below the same way: as a structured way to evaluate whether eggs fit within your own biology & your goals:

Here’s how to make that assessment for yourself

The framework below helps you assess your current inflammatory status, lipid sensitivity, immune reactivity, and metabolic context.

This same 6-part consideration applies whether you’re considering eggs or any other food with potential inflammatory or lipid effects

Inflammatory Status & Immune Response

Lipid Metabolism & Cardiovascular Risk

Gut Health & Digestive Function

Metabolic & Hormonal Context

Physical & Cognitive Response Patterns

Nutritional Replacement Strategy

Here’s my 6-Part Protocol for Stubborn Inflammation & Lipid Markers to help you assess food-specific inflammatory and lipid responses. so you can build a precision nutrition approach that matches your biomarkers and risk profile without relying on popular opinion or what worked for someone else even if you’re already eating “clean” & still not seeing the results you want:

If you would like to Access the The Vault Food-Inflammation Audit: A 6-Part Protocol for Stubborn Inflammation & Lipid Markers as a one-time option (without an ongoing subscription), you can access that here:

You shouldn’t have to watch your markers drift in the wrong direction because universal nutrition advice doesn’t address individual variability. With The Vault Food-Inflammation Audit, you won’t.