"My LDL-C is 186—I eat whole foods & exercise: what else is left to do?"

What to check before telling yourself “my LDL-C is just genetic”

➤ A client asked recently “I just received my blood test results and am very surprised at the high LDL-C levels, because I consider myself fit and healthy and have been for years.

I’m 5’11”, 186 lbs at ~10% body fat. My diet is basically all whole foods with healthy fats, fatty fish, eggs, nuts, avocados, red meat, etc. I weight train 2-3 days a week, cardio 2 days a week. I rarely have anything processed and don’t really eat out. I have no family history of high cholesterol or early heart disease.

Should I be concerned with the LDL-C & APOB levels below? Should I consider changing anything in my diet or lifestyle to lower these to a normal range?

Apolipoprotein B (APOB) 128 mg/dl

Lipoprotein (a) 29 nmol/L

LDL-C 186 mg/dL

—I’m trying to understand whether there’s anything meaningful left to do with lifestyle or are statins my only option here?”

That question is so much more common than we might think—especially among high-agency clean eaters.

So in this article, we will look at:

Why elevated LDL-C and ApoB matter even when you are otherwise healthy

How to separate genetic contributors from lifestyle-related ones

What to examine in a clean lifestyle before you conclude medication is the only path

The cholesterol-disposal pathway that many healthy eaters haven’t addressed

Let’s get started.

Fatty streaks and early atherosclerotic lesions start in our 20s and 30s

If you’re entertaining a statin conversation, it’s first worth pausing on why LDL-C and ApoB matter at all, especially in an otherwise generally healthy individual.

LDL-C and ApoB matter because CVD risk is driven by this: the longer artery walls are exposed to atherogenic particles, the more opportunity there is for retention and plaque development.

The core idea is cumulative exposure over time:.

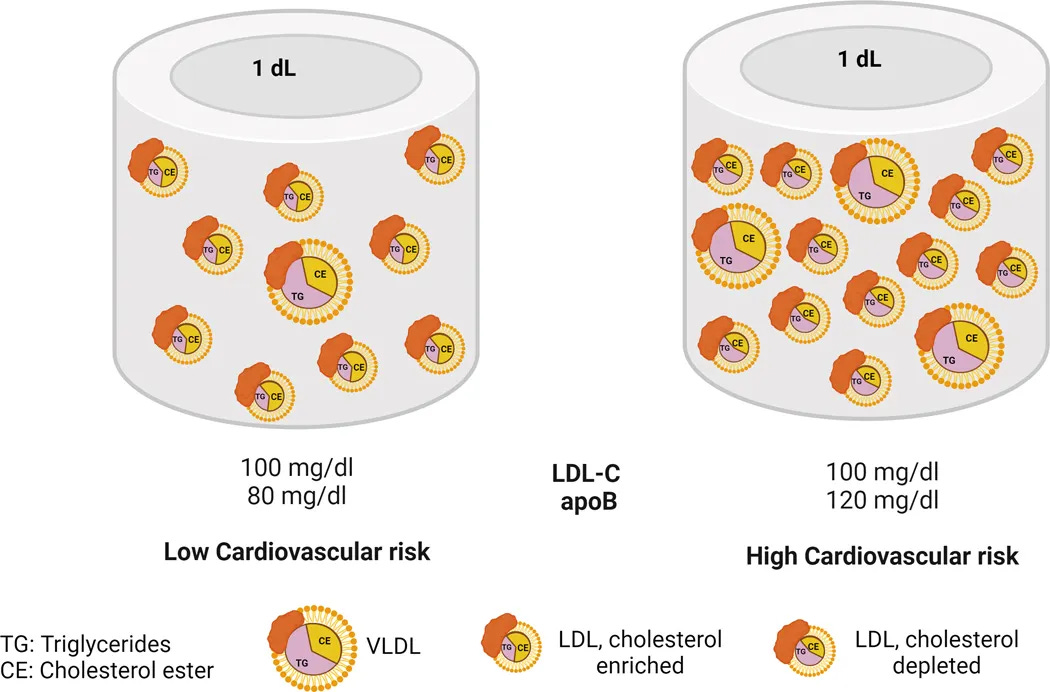

ApoB is especially useful here because it tracks the number of atherogenic particles (not just the cholesterol mass inside them), and lower ApoB maintained over longer periods consistently links to lower adverse cardiovascular event rates.

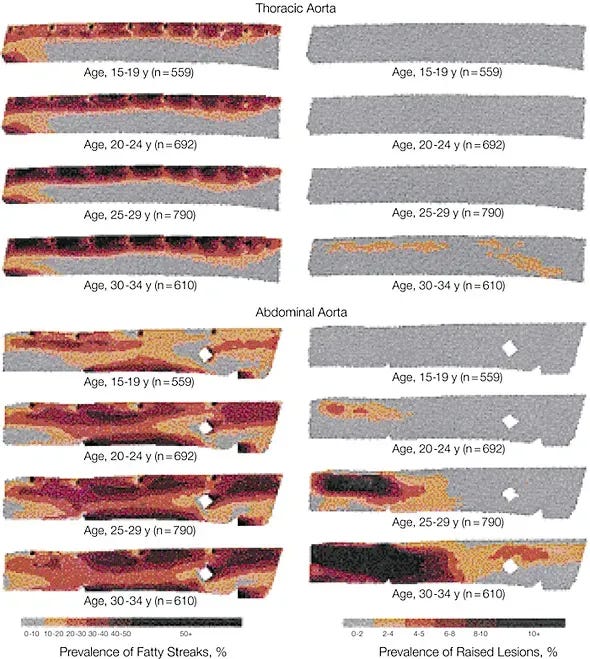

The uncomfortable part is that atherosclerosis does not begin at retirement age.

Autopsy-based research in younger adults show that fatty streaks and early atherosclerotic lesions are already present in a meaningful fraction of individuals in their 20s and 30s.

By the time we are in midlife or beyond with an elevated LDL or ApoB, we are not starting the clock; we are looking at a curve that has been running for decades.

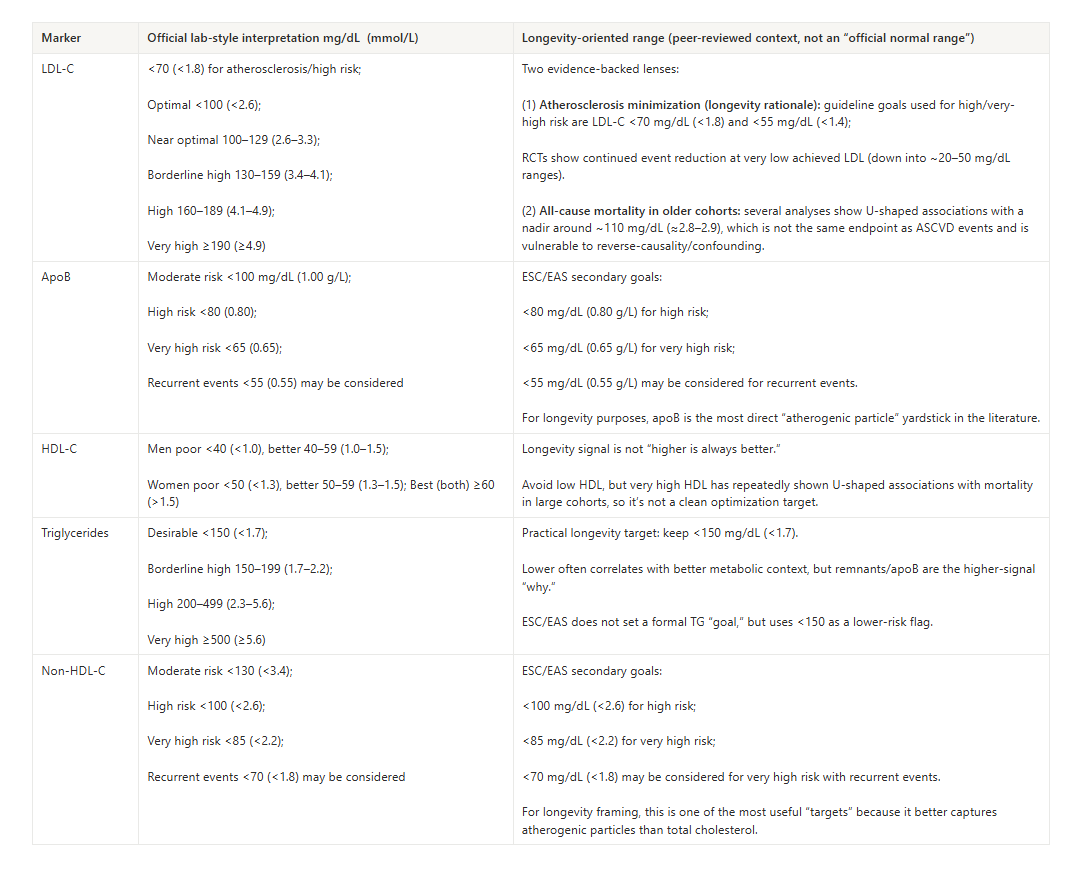

When we line numbers up, there are really two different sets of “ranges” in play:

Guideline-oriented ranges that affect who qualifies for medication

Prevention- or longevity-oriented ranges that aim for lower long-term ApoB exposure, especially if your goal is not just “no event in the next 10 years,” but lower cumulative burden for the rest of your life

Once that context is set, the important question becomes less “Is my elevated LDLC important?” and more,

“Given my specific pattern and numbers, what is driving this—and what is the smartest next step given my goals?”

An excellent lifestyle does not guarantee an optimal lipid panel.

When LDL-C or ApoB stays elevated despite strong habits, an important step is to rule in/out the genetic contributors.

Here’s what you can check:

ApoE4 genetics

ApoE4 carriers can show larger LDL-C responses to dietary fat changes than non-carriers, even when the food quality is high.

Familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) suspicion pattern

When saturated fat intake is genuinely low (not assumed low) but LDL-C remains very elevated, inherited lipid biology becomes a stronger suspect.

Lp(a) levels

Lp(a) is a genetically driven risk factor; lifestyle tends to have little effect on the level itself, which is why clean living doesn’t necessarily normalize it.

When one or more of the above is in play, advanced testing and clinician-guided options (including medication options) may be a reasonable step to incorporate.

Next steps worth considering:

ApoE genotype testing

Lp(a) measurement (once-in-life is commonly recommended in preventive cardiology contexts)

Coronary calcium scoring and/or other imaging (context-dependent, age/risk dependent)

Cardiology consult if FH is suspected, or if LDL-C is very high

In someone with clear FH, very high Lp(a), or established plaque, these steps often flow naturally into a medication conversation, with lifestyle as the non-negotiable foundation underneath.

In the client example, the opposite was true: Lp(a) was normal, FH seemed unlikely, and there was no strong family history of early cardiovascular disease.

So the next question became, specifically:

What in their day-to-day pattern is still driving ApoB and LDL-C this high?

In my client’s situation, this analysis has to happen inside a pattern that already looks reasonably good: whole foods, low on processed foods, regular activity.

Saturated fats

This is usually the first place to look, even in clean diets. Gram totals can be higher than you think once you include:

Generous nut and nut butter portions, especially richer mixes.

Seeds and seed butters layered onto bowls and snacks.

Coconut products used for creaminess: coconut milk, yogurt, creamers, oil.

Dark chocolate and healthy chocolate snacks.

Full-fat dairy, cheese, butter, or ghee

Egg yolks and higher-fat cuts of animal protein.

If you have never looked at this as an actual gram total over a few typical days, it is easy to underestimate.

Does dietary cholesterol matter?

Dietary cholesterol sits slightly behind saturated fat in most people, but it is not irrelevant. For many, tightening saturated fat has a larger effect on LDL-C than changing cholesterol intake per se. For a subset of people—especially some ApoE4 carriers—very high intakes of egg yolks and certain organ meats can move LDL-C more.

Carbohydrate restriction pattern (LMHR phenotype check)

Lean Mass Hyper Responders (LMHR) can see large LDL-C increases on lower-carb/keto approaches despite improved metabolic markers, often in very lean, often low BMI, active people with low triglycerides and high HDL. This is typically reversible with dietary rebalancing.

So, the right next step depends on precise details—exactly what you eat and how much, your genetics, and how high your LDL-C/ApoB actually are (180 isn’t 600).

Often, a carefully executed lifestyle phase is enough to bring LDL-C and ApoB into a range that feels acceptable—especially when there is no FH pattern, high Lp(a), or established plaque. When those inherited or structural factors are present, the same lifestyle work still matters, but medications are potentially more likely to sit alongside it as part of a long-term plan.

However, for an individual without high Lp(a), without clear FH, and already on a minimally processed diet, there is one major lifestyle-modifiable factor for cholesterol reduction that is often left unexplored.

The cholesterol-disposal pathway that many healthy eaters haven’t addressed

That factor overlooked by most health conscious adults I work with (or in our Longevity Vault community), is how your gut and liver manage bile—and, through bile, how they clear or recycle cholesterol.

Bile acids as the “cholesterol exit pathway”

Your liver uses cholesterol to synthesize bile acids. Those bile acids are secreted into the small intestine to emulsify fats during digestion. Most of them are then reabsorbed in the distal small intestine and returned to the liver via enterohepatic circulation. This recycling loop is efficient: it lets the body reuse bile rather than constantly making it from scratch.

The catch is that this loop also sets the tone for how much cholesterol your liver needs to pull out of circulation.

If more bile acids are lost in the stool rather than recycled, the liver has to pull more cholesterol—partly from LDL particles—out of the bloodstream to make new bile. This is how bile acid sequestrants lower LDL-C: they bind bile acids in the gut so they cannot be reabsorbed, pushing the liver to clear more LDL-C to replenish its bile acid pool.

In sum, the implication is this:

If you increase bile acid excretion (instead of recycling), the liver must pull more cholesterol out of circulation to make new bile acids.

That tends to lower LDL-C and ApoB by increasing hepatic demand for cholesterol disposal.

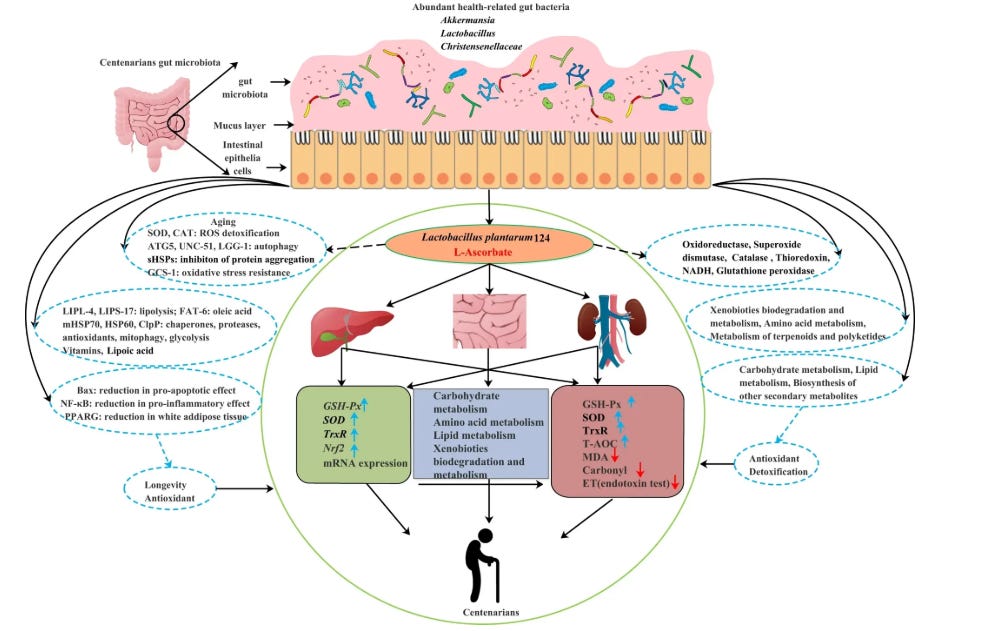

The importance of a diverse gut microbiome & beneficial longevity-supporting microbes

Bile isn’t just a digestion tool; it’s also an ecosystem signal.

Gut microbes modify bile acids (including through bile salt hydrolase activity), which changes the bile acid pool and can influence recycling behavior that affect lipid metabolism.

Microbial metabolites, including short-chain fatty acids, can also signal back to the liver and affect cholesterol synthesis and LDLC receptor expression.

Dysbiosis,

low diversity, or a

fiber pattern that does not support these beneficial microbes

—can tilt the system toward more recycling and fewer excretions, keeping LDLC higher than you would predict from a conventionally clean diet alone.

Some microbial patterns appear in healthier, longer-lived populations.

Higher levels of certain bacteria such as Akkermansia and selected Bifidobacteria, and lower levels of opportunistic gram-negative species, tend to be associated with better metabolic markers, lower inflammation, and more favorable lipid profiles in cohort data.

At the other end of the spectrum, patterns dominated by inflammatory, endotoxin-producing organisms—such as certain Enterobacteriaceae, Bilophila, and Desulfovibrio species—are linked with insulin resistance, fatty liver, and less favorable cholesterol handling.

A key point is that these more favorable microbes are not supported by generic “fiber” alone, but by a mix of fermentable fibers and polyphenol-rich plant foods. That mix shapes the SCFA profile, bile acid transformations, and barrier integrity that allow the gut to help the liver keep LDL-C and ApoB in a better range.

This is one reason why, genetics aside, two people can eat a similar healthy diet and have different LDLC/ApoB profiles: their disposal machinery and microbial handling are different.

Why psyllium isn’t enough: ‘More’ psyllium ≠ fiber diversity

Psyllium can be helpful, but “I take psyllium” is fundamentally not a substitute for a diverse fiber pattern regardless of how much you take.

It is a single fiber type, which means it addresses mainly only one cholesterol-clearance pathway. Fiber diversity is different.

A diverse fiber intake delivers multiple carbohydrate structures that different microbes specialize in breaking down, producing a wider set of fermentation outputs and shifting how bile acids are transformed, recycled, and signaled.

That is why the “gut /LDLC / bile” layer is not improved or solved by increasing one supplement. It is solved by changing the substrate environment the gut ecosystem runs on.

Common reasons it under-delivers:

1) Different fibers feed different microbes because microbes are specialists

Most gut bacteria are not generalists. They’re built to break down specific carbohydrate structures.

Psyllium mostly supplies one dominant structure.

A diverse fiber intake supplies many different fiber types and fractions (beta-glucans, pectins, resistant starches, inulin-type fructans, and many others).

If you feed the gut a single substrate, you mainly expand the microbes that can use that one substrate. You do not build a broad, resilient, longevity-supporting community that includes the species associated with better metabolic health and lower LDL-C.

2) All fibers are not the same & different fibers produce different metabolic outputs

What matters in human physiology is not “fiber” as a category; it’s what each specific fiber becomes after microbes process it.

Different foods emphasize different fibers and different fibers are different molecules such as:

Beta-glucans

Arabinoxylans and other hemicelluloses

Pectins, including rhamnogalacturonans

Inulin-type fructans

Galacto-oligosaccharides

Resistant starch (5 types, RS1-RS5)

Galactomannans and glucomannans

Cellulose-lignin structural fibers

And that’s still not the full catalog: xyloglucans, arabinans, galactans, xylans, and other pectin side chains and hemicellulose variants are common across plant foods, and each behaves differently in the gut. These differences matter because:

Different fibers yield different short-chain fatty acid profiles (different balances of butyrate, propionate, and acetate).

Different fibers support different cross-feeding chains, where one microbe breaks material down and another converts it into a metabolite that acts in the gut or reaches the liver.

Psyllium can support some fermentation, but again it does not replicate the output diversity you get from a mixed substrate environment.

3) Psyllium hits one bile lever; diversity hits multiple bile levers

The gut influences cholesterol disposal through several processes:

Process A: bile acid binding and excretion (viscosity and gel formation)

Process B: microbial bile transformations (which change which bile acids circulate and how they signal)

Process C: transit time and stool architecture (how long bile acids sit in the gut available for reabsorption)

Process D: gut barrier and mucus ecology (which influences microbial composition and metabolite production)

Psyllium is mainly a Process A tool. Fiber diversity moves A, B, C, and D. So psyllium can be useful, but it’s not the same category of strategy.

4) Whole-food fiber is a “matrix,” not an isolated ingredient

Plant foods deliver fiber bundled with:

polyphenols

minerals

organic acids

water-binding structures

intact cell walls

Microbes don’t just respond to “grams.” They respond to the physical and chemical environment the fiber arrives in.

Psyllium is an extracted component. It can’t recreate the effects of a varied plant-food pattern.

If the goal is to shift the gut environment that governs bile recycling and cholesterol removal, you need multiple fiber families feeding longevity-supporting microbes, while diluting and crowding out more inflammatory species.

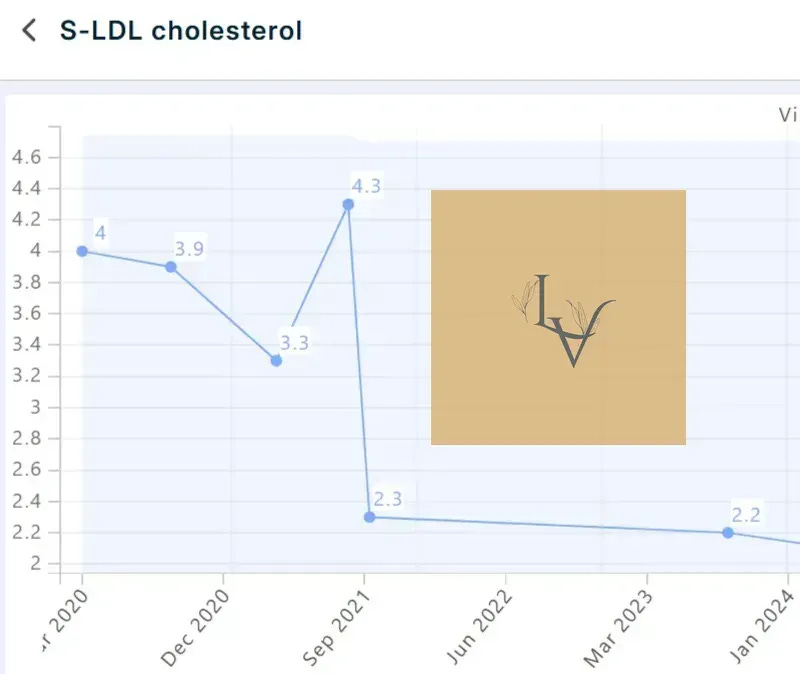

How I Decreased My LDL-C in 6 Weeks

For context, my LDL-C had lived in the 3.8–4.3 mmol/L range for years, despite being plant-leaning, exercising, and keeping obvious saturated fat in check.

I was not starting from a standard Western baseline.

What changed was one core strategy

I stopped treating fiber as a single nutrient and layered in a gut–bile–cholesterol approach that support longevity-leaning, beneficial microbes and give less room to more inflammatory species.

Below, you can see my actual LDL-C labs over a 5 year period.

The jump to 166 mg/dL (4.3 mmol/L) is the point just before I implemented that gut–LDL approach. Six weeks later, LDL-C was around 89 mg/dL (2.3 mmol/L), and on subsequent tests it has stayed in the low-2s mmol/L range (~77–85 mg/dL),

In my case, that shift represented roughly a 45–50% reduction in LDL-C on top of an already good lifestyle—by making bile handling and longevity-supporting microbial patterns a central cholesterol-clearance strategy.

That doesn’t mean everyone will see the same numbers. It also doesn’t mean that you won’t.

It does mean that, if you’re already doing the obvious things and your LDL-C or ApoB still sits higher than you’d like, there is a difference between:

“I tried psyllium, and eat vegetables” VS.

“I deliberately rebuilt my fiber pattern to feed beneficial, longevity-supporting microbes and improve bile-driven cholesterol handling.”

Warmly,

—Kat

P.S. In 1:1 work, this is the step-by-step we map when someone has “good” habits, elevated LDL-C or ApoB, and a strong interest in preserving long-term cardiovascular and brain health.

Instead of just ‘eat more fiber,’ we deliberately target the gut–bile–microbiome environment to favor longevity-supporting microbes and more efficient cholesterol clearance.

That full process is now in:

The 5-Phase Gut-LDL-C Blueprint for Lower Cholesterol + Reduced Cardiovascular Risk

It gives you the same structured gut–bile–LDL approach I would normally work through across multiple sessions, but in a format you can implement at your own pace.

You can pick it up as a standalone solution above, or get access to it (along with other implementation-level longevity tools like this) when you upgrade to Vault Insider Exclusive (this is the highest paid tier, not the regular paid tier).

All my digital solutions are updated regularly: The 5-Phase Gut-LDL-C Blueprint (based on 70+ peer reviewed articles) was just updated to incorporate the latest data on longevity-promoting microbes and how to support them. All existing owners and Vault Insiders automatically have access to the new edition, and that access remains active even as new editions are released at higher investment levels.

This is accessed through a private link to the Dashboard (shown below) you receive, so you’re getting a structured & live digital resource—not a static PDF file:

You shouldn’t have to treat statins as the only “serious” next step when lifestyle hasn’t moved your numbers; with The 5-Phase Gut-LDL-C Blueprint, you won’t.

References

Strong JP et al. Prevalence and extent of atherosclerosis in adolescents and young adults: implications for prevention from the Pathobiological Determinants of Atherosclerosis in Youth Study. JAMA. 1999 Feb 24;281(8):727-35.

Díaz Perdigones CM et al. Taxonomic and functional characteristics of the gut microbiota in obesity: a systematic review. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr (Engl Ed). 2025 Nov;72(9):501624.

Singh P et al. Implications of the gut microbiome in cardiovascular diseases: association of gut microbiome with cardiovascular diseases, therapeutic interventions and multi-omics approach for precision medicine. Medical Microbiology. 2023.

Wu L et al. Gut microbiota as an antioxidant system in centenarians associated with high antioxidant activities of gut-resident Lactobacillus. npj Biofilms Microbiomes. 2022;8:102.

Benjamin EJ et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2018 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018;137(12):e67-e492.

Cui X et al. Metagenomic and metabolomic analyses unveil dysbiosis of gut microbiota in chronic heart failure patients. Sci Rep. 2018 Jan 12;8(1):635.

Wang Z et al. Non-lethal inhibition of gut microbial trimethylamine production for the treatment of atherosclerosis. Cell. 2015 Dec 17;163(7):1585-95.

Poland JC et al. Bile acids, their receptors, and the gut microbiota. Physiology (Bethesda). 2021 Jul 1;36(4):235-245.

Razavi AC et al. High-density lipoprotein cholesterol in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk assessment: exploring and explaining the U-shaped curve. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2023 Dec;25(12):1725-1733.

Zhou Z et al. Low-density-lipoprotein cholesterol and mortality outcomes among healthy older adults: a post hoc analysis of ASPREE trial. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2024 Apr 1;79(4):glad268.

De Oliveira-Gomes D et al. Apolipoprotein B: bridging the gap between evidence and clinical practice. Circulation. 2024 Jul 2;150(1):62-79.

Ghavami A et al. Soluble fiber supplementation and serum lipid profile: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Adv Nutr. 2023 May;14(3):465-474.

Dahl WJ et al. Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: health implications of dietary fiber. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2015 Nov;115(11):1861-70.

Svilaas T et al. High levels of lipoprotein(a) – assessment and treatment. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2022 Dec 16;142(1).

Gaba P et al. Association between achieved low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels and long-term cardiovascular and safety outcomes: an analysis of FOURIER-OLE. Circulation. 2023 Apr 18;147(16):1192-1203.

Grundy SM et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: executive summary. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019 Jun 25;73(24):3168-3209.

Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaboration et al. Efficacy and safety of more intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol: a meta-analysis of data from 170,000 participants in 26 randomised trials. Lancet. 2010 Nov 13;376(9753):1670-81.

Ference BA et al. Effect of long-term exposure to lower low-density lipoprotein cholesterol beginning early in life on the risk of coronary heart disease: a Mendelian randomization analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012 Dec 25;60(25):2631-9.

Sabatine MS et al. Evolocumab and clinical outcomes in patients with cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2017 May 4;376(18):1713-1722.

Schwartz GG et al. Alirocumab and cardiovascular outcomes after acute coronary syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2018 Nov 29;379(22):2097-2107.

Zhou Z et al. Low-density-lipoprotein cholesterol and mortality outcomes among healthy older adults: a post hoc analysis of ASPREE trial. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2024 Apr 1;79(4):glad268.

Chwal BC et al. On-target low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in adults with diabetes not at high cardiovascular disease risk predicts greater mortality, independent of early deaths or frailty. J Clin Med. 2024 Dec 16;13(24):7667.

Madsen CM et al. Extreme high high-density lipoprotein cholesterol is paradoxically associated with high mortality in men and women: two prospective cohort studies. Eur Heart J. 2017 Aug 21;38(32):2478-2486.

Jacobson TA et al. National Lipid Association recommendations for patient-centered management of dyslipidemia: Part 2. J Clin Lipidol. 2015 Nov–Dec;9(6 Suppl):S1-122.e1.

Gidding SS et al. Pathobiological Determinants of Atherosclerosis in Youth (PDAY) Risk Score in young adults predicts coronary artery and abdominal aorta calcium in middle age: the CARDIA Study. Circulation. 2016 Jan 12;133(2):139-46.

Sniderman AD et al. Apolipoprotein B particles and cardiovascular disease: a narrative review. JAMA Cardiol. 2019 Dec 1;4(12):1287-1295.

Giugliano RP, et ak; FOURIER Investigators. Clinical efficacy and safety of achieving very low LDL-cholesterol concentrations with the PCSK9 inhibitor evolocumab: a prespecified secondary analysis of the FOURIER trial. Lancet. 2017 Oct 28;390(10106):1962-1971.