➤ Someone recently asked me this question, and it captures a challenge many people never find the right answer for:

"But, Kat, how do you manage to fall back asleep?"

They assumed there was a single trick — some breathing pattern, a magic tea, a special routine.

They'd already tried the usual fixes: blackout curtains, no screens at night, melatonin, caffeine detox, even prescription sleep aids.

Nothing worked.

Why Falling Back Asleep Is Less About Technique—and More About Your Baseline

Most people think of falling back asleep as something you do.

In reality, the deciding factor is whether your body can shift gears into a low-arousal, sleep-permissive state on its own.

That capacity isn't built in the moment. It's shaped by what your system has been exposed to over the previous hours — and in some cases, days.

1. Reframing the Question

If you're waking in the night and can't fall back asleep, the real question isn't "What should I try right now?"

It's "Has my nervous system been set up to re-enter recovery states without conscious effort?"

Why This Reframe Changes Everything

Most people approach middle-of-night waking as an acute problem requiring an immediate solution. This creates a fundamental mismatch between the timeline of the problem (seconds to minutes) and the timeline of the actual solution (hours to days of nervous system preparation).

Sleep reinitiation is a neurobiological capacity, not a skill you can deploy on demand.

When it happens automatically, it's because your brainstem sleep-wake switching circuits can override cortical arousal without conscious intervention. When you ask "What should I try right now?" you're essentially asking your conscious mind to solve a problem that can only be resolved by unconscious, automatic processes.

This is about sleep capacity, not sleep technique.

2. The Baseline Factor

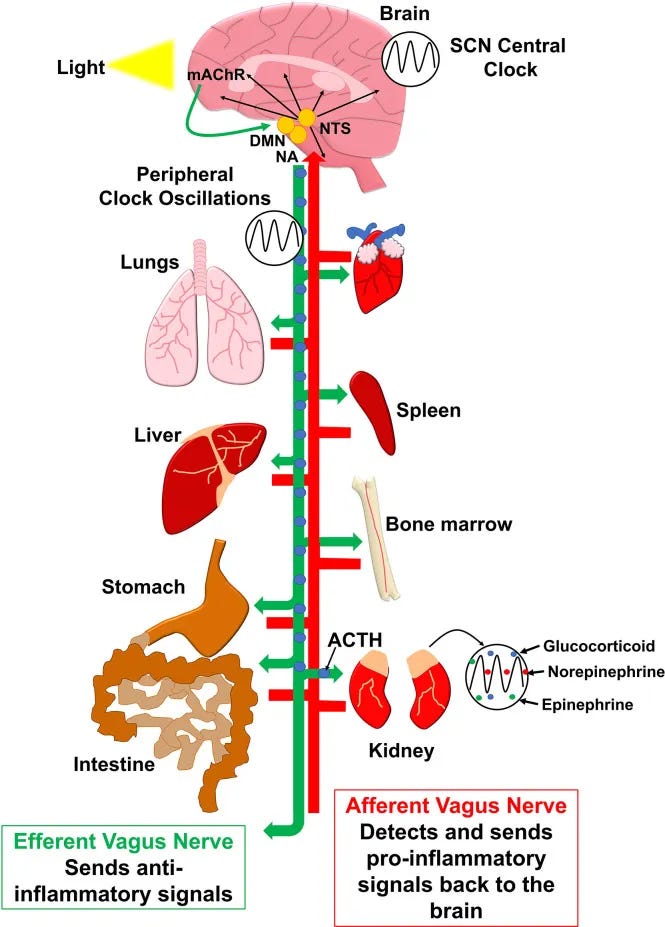

Your parasympathetic state — the body's built-in "rest mode" — is what allows you to downshift naturally after a middle-of-night wake-up.

But parasympathetic capacity isn't just about relaxation.

It's specifically about your autonomic nervous system's ability to rapidly shift from sympathetic activation back to vagal dominance under the pressure of sleep debt and circadian vulnerability.

Research shows that higher heart‑rate variability (HRV)—a marker of stronger parasympathetic (vagal) tone—is associated with smoother sleep stage transitions and better overall sleep quality. Low HRV before sleep predicts more fragmented and less restorative sleep.

When this baseline parasympathetic tone is strong, waking briefly at night is followed by an almost automatic return to sleep.

When it's compromised, you can be exhausted and still stay awake, because your brain remains too close to its alert threshold.

3. What Shapes This Capacity Over Time

Autonomic flexibility during waking hours: Your nervous system's switching capacity gets stronger with specific types of controlled stress-recovery cycles during the day. Brief, intense activation followed by complete recovery periods builds the neural pathways needed for rapid state transitions at night.

Conversely, chronic low-grade activation without recovery periods — prolonged mental work, background stress, or stimulation without downtime — weakens your system's ability to access deeper parasympathetic states when needed.

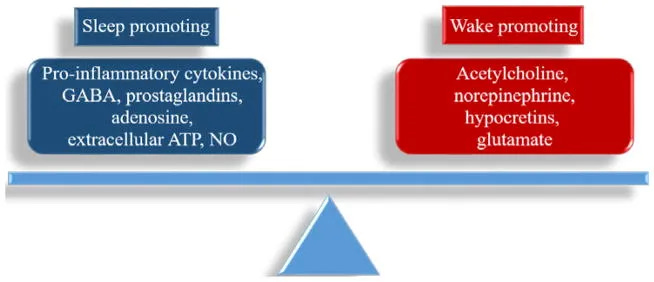

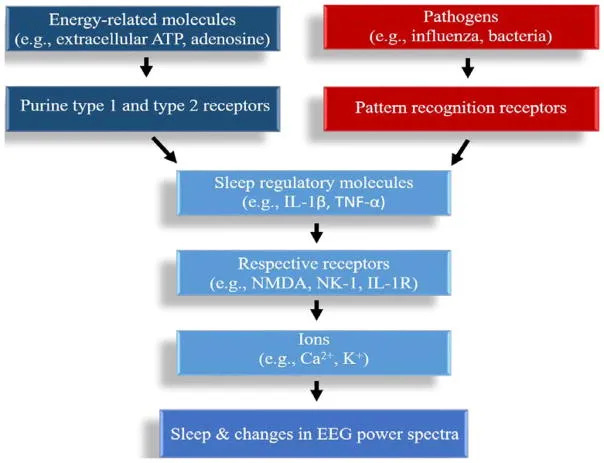

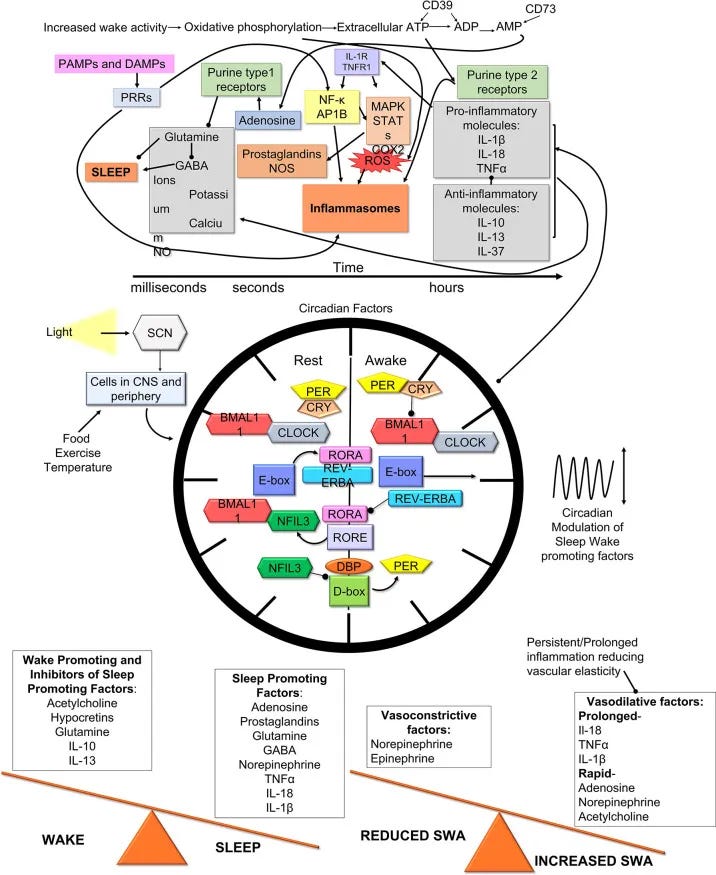

Inflammatory interference patterns: Even subclinical inflammation from poor recovery, chronic stress, or metabolic dysfunction can elevate cytokine levels enough to interfere with the delicate neurotransmitter balance required for smooth sleep reinitiation.

Studies show that individuals with elevated inflammatory markers have significantly longer wake episodes during the night, regardless of their sleep hygiene practices.

Recovery signal processing: Unresolved mental activation, late-night stimulation, or circadian misalignment keep neural circuits active past the point they should naturally quiet, interfering with your brain's ability to process "return to sleep" cues during vulnerable transition periods.

These aren't just "habits." They're inputs that either strengthen or weaken the ease of returning to deeper stages once you're awake.

4. The Counterintuitive Revelation -

Why Nighttime Efforts are Biochemically Counterproductive

When you wake in the middle of the night, you're not simply "out of sleep." You've broken out of a finely tuned biological sequence called sleep architecture — and that's why standard interventions often don't work.

One of the reasons is this: effort adds noise to the system

Breathing drills or relaxation techniques can work if you're already near the re-entry threshold — but if baseline arousal is too high, these can paradoxically keep prefrontal circuits engaged.

The biological mechanisms behind this paradox are more complex than most people realize:

Adenosine Receptor Sensitivity Creates a Neurochemical Catch-22

Adenosine promotes sleep by binding to A1 and A2A receptors in the basal forebrain and hypothalamus, inhibiting wake-promoting neurons. But receptor sensitivity varies dramatically based on your recent sleep history and metabolic state.

When your adenosine system is already compromised—from chronic sleep restriction, caffeine interference, or inflammatory cytokines— these pathways may be more easily influenced by competing arousal signals.

Conscious effort activates glutamate and dopamine pathways that can counteract adenosine’s sleep-promoting effects.

The result is that mental effort doesn’t just fail to promote sleep — it may further bias the system toward wakefulness. This could help explain why people with chronic insomnia often report feeling “more awake” the harder they try, even when objectively exhausted.

Prostaglandin Cascades Turn Mental Effort Into Inflammatory Wake Signals

Stress or sustained cognitive load can influence inflammatory signaling through the cyclooxygenase (COX) pathway, affecting the balance of prostaglandin E₂ (PGE₂) and prostaglandin D₂ (PGD₂) production in the brain.

Under normal conditions, PGD₂ promotes sleep by acting on the ventrolateral preoptic area (VLPO) — your brain’s primary sleep switch. But in a compromised state, an increased PGE₂-to-PGD₂ ratio can shift the system toward wakefulness.

Microglial Activation Creates Neuroinflammatory Sleep Resistance

The emotional frustration and cognitive load of "working at" sleep can activate microglia—the brain's immune cells—specifically in the hypothalamus and basal forebrain where sleep circuits are located.

Activated microglia release pro-inflammatory cytokines including interleukin-1β (IL-1β), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and interleukin-6 (IL-6). These cytokines functionally inhibit GABA signaling in sleep-promoting neurons while simultaneously enhancing glutamate-mediated arousal circuits.

This creates a state of "neuroinflammatory insomnia" where your sleep centers are actively suppressed by immune activation. The effect can persist for hours after the initial stress, explaining why a brief period of sleep effort may affect the entire night.

Research shows that people with chronic insomnia have elevated microglial activation markers in sleep-regulatory brain regions, suggesting this mechanism becomes self-perpetuating with repeated sleep effort.

Thermoregulatory Disruption Shifts Your Entire Circadian Window

Your natural circadian rhythm includes a precisely timed drop in core body temperature—the circadian temperature minimum—that occurs around 4-6am and facilitates sleep reinitiation during this period.

This temperature drop is mediated by peripheral vasodilation, particularly in the hands and feet, which allows heat dissipation from the core. The process is parasympathetically driven and can be disrupted by sympathetic activation.

Sustained mental effort can maintain mild sympathetic activation, which may reduce the vasodilation needed for core temperature drop, making it harder to re-enter sleep during this window.

The Neurochemical Perfect Storm

These mechanisms don't operate in isolation—they may interact to create a self-reinforcing arousal state:

Mental effort → glutamate release → microglial activation → cytokine production → prostaglandin imbalance → reduced adenosine effectiveness → sympathetic activation → temperature dysregulation → sustained wakefulness

The result: you're "working at" sleep while simultaneously triggering every major biological system that maintains wakefulness.

This explains why the same breathing technique that helps us fall asleep at bedtime can keep us awake at 3am—the underlying biological context has changed, and conscious effort now becomes neurochemically counterproductive.

This is why building reinitiation capacity during the day, rather than deploying techniques at night, becomes the foundational & viable long-term solution.

The Bottom Line

By the time you're trying something at 3 a.m., your nervous system flexibility, transition vulnerability, and physiological baseline have already determined the outcome. Without addressing those inputs ahead of time, very little in-the-moment tactic can reliably restore the night's natural progression.

5. How to Build Sleep Reinitiation Capacity During the Day (Not at 3 AM)

Once I understood this, everything changed about how I approached middle-of-night waking. Instead of focusing on what to do when I woke up, I started focusing on what would make falling back asleep automatic.

The ability to fall back asleep is built during the day, not earned at night. This meant shifting from symptom management to sleep capacity building.

Rather than tracking just sleep duration, I started tracking how long it took me to re-enter deeper stages after a wake-up.

If that time consistently stayed long, it told me my system's baseline wasn't set right.

3 Core Capacities That Make Sleep Reinitiation Automatic

Instead of another sleep hygiene checklist, here are a few of the core capacities that help with easier sleep reinitiation:

Autonomic flexibility training: Use controlled stress-recovery cycles during the day to strengthen your nervous system's switching ability. This might include breath work with specific ratios, cold-heat contrast therapy, or high-intensity exercise followed by complete rest periods. Everything timed properly. These weren't just recovery tools; they were training my brain's capacity to rapidly shift states under pressure.

Recovery signal optimization: Address inflammatory inputs, metabolic stability, and circadian alignment so your brain can clearly process "return to sleep" signals. This can include adjusting factors like evening meal timing, light exposure patterns, or underlying inflammation.

Sleep architecture protection: Build consistent patterns that support natural sleep stage progression, so disruptions become brief rather than extended wake episodes. This involves understanding your individual circadian rhythm and adenosine patterns, then aligning daily activities to support rather than undermine these biological cycles.

The key insight was recognizing that there are multiple biological levers beyond bedtime habits—but knowing which lever to adjust first, and in what sequence, makes all the difference.

Falling back asleep isn't about a secret technique or just perfect environment.

It's about whether your nervous system was prepared before you even got into bed.

That preparation isn't left to chance.

It's shaped by how you handle stress recovery, autonomic flexibility, and system readiness—so your brain knows exactly when to stay in restorative stages.

Moving Beyond Sleep Hygiene

Once I stopped focusing only on sleep onset and started looking at what was disrupting continuity, my sleep became much more stable.

The breakthrough came from shifting perspective entirely—instead of asking "How do I fall asleep better?" I started asking "What's preventing my brain from staying in restorative stages?"

The solution wasn't another bedtime routine—it was understanding how sleep pressure, neurotransmitter balance, and circadian timing interact during those critical hours after 3am.

This meant tracking not just when I went to bed, but how different daytime activities affected my parasympathetic/sympathetic tone. It meant considering whether late afternoon light exposure was shifting my melatonin curve. It meant recognizing that my 7pm workout might be creating the wrong kind of arousal signal at the wrong time.

Subscribe to receive the Vault 5-Part Sleep Clarity Masterclass so you can sleep deeply, wake energized, and safeguard the lasting cognitive health and vitality to cook, garden, read, and play with your grandkids for decades to come:

Most importantly, it meant treating sleep as a biological system with measurable inputs and outputs, rather than something I could willpower my way through.

When I started testing variables systematically—adjusting one factor at a time and measuring sleep continuity rather than just duration—the 3am wake-ups finally started to resolve.

Warmly,

Kat

References

Hayaishi O, Urade Y. Prostaglandin D2 in sleep-wake regulation: recent progress and perspectives. Neuroscientist. 2002 Feb;8(1):12-5. doi: 10.1177/107385840200800105. PMID: 11843094.

Urade Y, Hayaishi O. Prostaglandin D2 and sleep/wake regulation. Sleep Med Rev. 2011 Dec;15(6):411-8. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2011.08.003. PMID: 22024172.

Krauchi K, Deboer T. The interrelationship between sleep regulation and thermoregulation. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed). 2010 Jan 1;15(2):604-25. doi: 10.2741/3636. PMID: 20036836.

Raymann RJ, Swaab DF, Van Someren EJ. Skin temperature and sleep-onset latency: changes with age and insomnia. Physiol Behav. 2007 Feb 28;90(2-3):257-66. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.09.008. Epub 2006 Oct 27. PMID: 17070562.

Harding EC, Franks NP, Wisden W. Sleep and thermoregulation. Curr Opin Physiol. 2020 Jun;15:7-13. doi: 10.1016/j.cophys.2019.11.008. PMID: 32617439; PMCID: PMC7323637.

Harding EC, Franks NP, Wisden W. The Temperature Dependence of Sleep. Front Neurosci. 2019 Apr 24;13:336. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2019.00336. PMID: 31105512; PMCID: PMC6491889.

Leenaars CHC, Savelyev SA, Van der Mierden S, Joosten RNJMA, Dematteis M, Porkka-Heiskanen T, Feenstra MGP. Intracerebral Adenosine During Sleep Deprivation: A Meta-Analysis and New Experimental Data. J Circadian Rhythms. 2018 Oct 9;16:11. doi: 10.5334/jcr.171. PMID: 30483348; PMCID: PMC6196573.

Porkka-Heiskanen T, Strecker RE, Thakkar M, Bjorkum AA, Greene RW, McCarley RW. Adenosine: a mediator of the sleep-inducing effects of prolonged wakefulness. Science. 1997 May 23;276(5316):1265-8. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5316.1265. PMID: 9157887; PMCID: PMC3599777.

Rowe RK, Green TRF, Giordano KR, Ortiz JB, Murphy SM, Opp MR. Microglia Are Necessary to Regulate Sleep after an Immune Challenge. Biology (Basel). 2022 Aug 19;11(8):1241. doi: 10.3390/biology11081241. PMID: 36009868; PMCID: PMC9405260.

Stockwell J, Jakova E, Cayabyab FS. Adenosine A1 and A2A Receptors in the Brain: Current Research and Their Role in Neurodegeneration. Molecules. 2017 Apr 23;22(4):676. doi: 10.3390/molecules22040676. PMID: 28441750; PMCID: PMC6154612.

Reichert CF, Deboer T, Landolt HP. Adenosine, caffeine, and sleep-wake regulation: state of the science and perspectives. J Sleep Res. 2022 Aug;31(4):e13597. doi: 10.1111/jsr.13597. Epub 2022 May 16. PMID: 35575450; PMCID: PMC9541543.

Zielinski MR, McKenna JT, McCarley RW. Functions and Mechanisms of Sleep. AIMS Neurosci. 2016;3(1):67-104. doi: 10.3934/Neuroscience.2016.1.67. Epub 2016 Apr 21. PMID: 28413828; PMCID: PMC5390528.

Zielinski MR, Gibbons AJ. Neuroinflammation, Sleep, and Circadian Rhythms. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022 Mar 22;12:853096. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2022.853096. PMID: 35392608; PMCID: PMC8981587.